Imran Khan’s Fall and the Democratic Backsliding of Pakistan

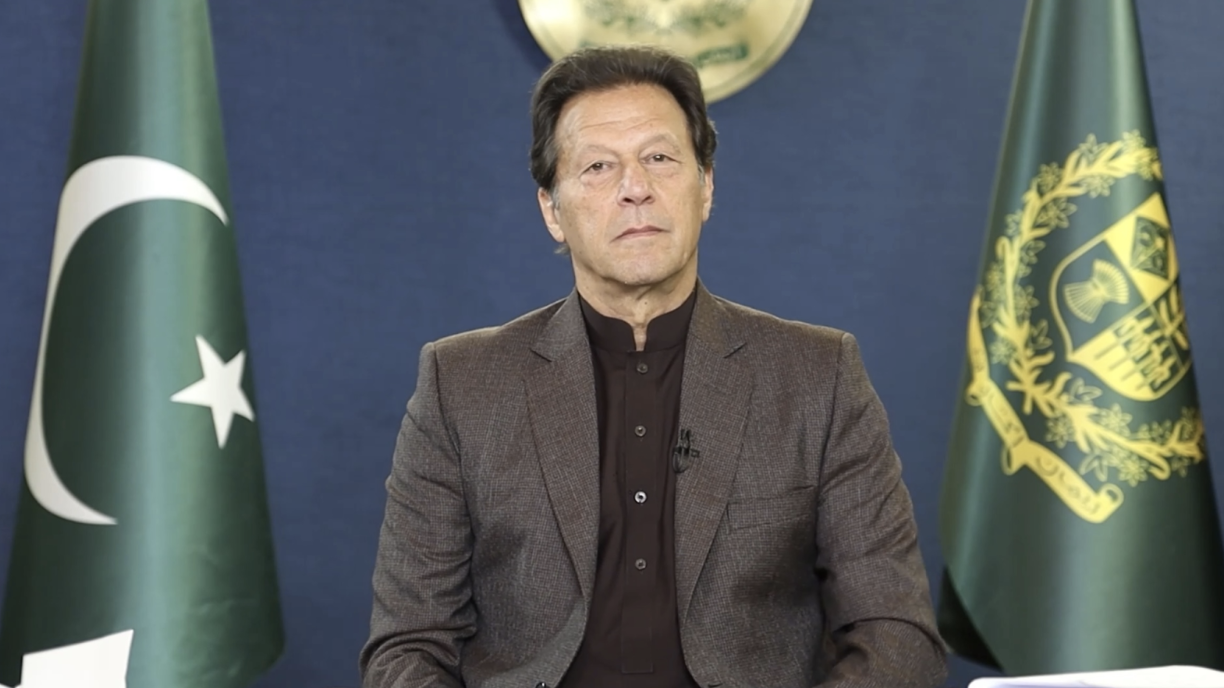

Photo courtesy of Imran Khan, via Wikimedia Commons. Licensed under CC BY 3.0.

On August 5th, 2023, cameras crowded outside a courthouse in Lahore as police arrested populist politician Imran Khan for allegedly using his position as prime minister to buy and sell state gifts worth 140 million Pakistani rupees, roughly half a million U.S. dollars. The country was in uproar within hours. Protests erupted nationwide, social media flooded with outrage, and the military tightened its grip. On December 20th, 2025, he was sentenced to 17 years in prison. More than the fall of a single political figure, Khan’s arrest exemplified the broader pattern of democratic backsliding that has been taking place in Pakistan for decades.

Pakistan’s persistent cycle of democratic instability is characterized by military dominance and the entrenchment of hereditary political dynasties, which consistently undermine elected officials. The fragile democratic system is rooted in colonial practices that concentrate power among elites while denying the working class a fair electoral process, underscoring the urgent need for structural democratic reform.

The cyclical rise and fall of democratic leaders and military dictators highlights a pattern in which elected governments in Pakistan function only within boundaries set by the military, not by constitutional authority. The pattern is well evidenced by the military coups of 1958, 1969, 1977, and 1999, all of which were followed by periods of autocratic military rule. Behind the scenes, the military also manipulates leadership transitions, determining which civilian governments are allowed to assume power and which ones are quietly silenced. Khan’s trajectory mirrors that of Zulfikar Ali Bhutto and Benazir Bhutto (PPP), both popular figures who ultimately met similar fates to Khan. Disagreements regarding foreign policy, senior military appointments, and a public dispute over the appointment of an intelligence official weakened Khan’s parliamentary majority, ultimately resulting in his overthrow and unjust imprisonment. While Khan sought to chart an independent course, particularly in foreign policy and senior military appointments, the military sought to maintain its traditional control over these domains and expected a civilian leader like Khan to comply without objection.

Virtually no elected leader has been able to govern Pakistan without heavy military interference. Khan’s rise to power was no exception. His imprisonment can be considered an inevitable outcome of a system in which the military, the judiciary, and pliant institutions collaborate to maintain a facade of democracy while retaining control. Khan’s downfall was therefore not the product of individual missteps. Like past civilian leaders, he remained secure only as long as his agenda aligned with the military’s political calculus.

Initially, the military supported Khan because his populist party platform weakened entrenched rivals, including the Pakistan Muslim League–Nawaz (PML-N) and the Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP). As an elite, dynastic party, the PPP has long been vulnerable to military manipulation, with Benazir Bhutto’s (PPP) governments twice overthrown with military backing. Similarly, in the 1990s, the military funneled resources to weaken the PPP and support Nawaz Sharif (PML-N). Sharif’s rise in the 1980s was enabled by General Zia-ul-Haq’s patronage. Zia, himself, was a Pakistani military officer and politician who served as the sixth president of Pakistan after orchestrating a military coup. These parties function as hereditary enterprises, making them susceptible to military intervention, as leadership is structured around family networks that weaken internal democracy.

As a result, no prime minister in Pakistan’s 75-year history has completed a full five-year term, and civilian leaders remain vulnerable to removal whenever they challenge military interests, producing a structural pattern of democratic instability that Khan’s arrest merely exposes.

The structure of Pakistan’s political system, the elite-based parties, dynastic leadership, and military-dominated politics have created structural vulnerabilities that shape the evolution of Pakistan’s political parties. Although the PPP under the Bhuttos and the PML-N under the Sharifs both began as civilian-led political movements, they quickly became vehicles for elite consolidation, which left them vulnerable to military intervention whenever their agendas conflicted with the establishment’s interests. More than half of Pakistan’s parliamentary candidates are from dynastic backgrounds, meaning they are members of powerful political families that have held power across generations. Parties like the PPP and PML-N consistently recycle elite families rather than cultivate independent, qualified leadership. Nepotistic politics, reinforced by periodic military intervention, have prevented the development of strong, independent civilian institutions by continually disrupting political continuity, constitutional authority, and stable governance, which are necessary for civilian institutions to build expertise and legitimacy over time. It has reinforced a broader civil–military imbalance, making moments like Khan’s arrest symptoms of a deeper, systemic structure that repeatedly undermines democratic stability.

Hamza Alavi, a Pakistani sociologist at the University of Manchester, argues that postcolonial states like Pakistan’s democracy never had the chance to evolve into genuine popular sovereignty because the state inherited an “overdeveloped” military and bureaucracy from colonial rule. Military and bureaucratic institutions remain stronger than any elected government because they continue to control resources, decision-making, and continuity of power. The civil-military imbalance was only furthered by the occupation of Kashmir. The occupation enabled the Pakistani army to assume the role of guardian of national security, allowing the military to dominate politics and preventing civilian institutions from maturing. Thus, power remained concentrated among elite political families and senior bureaucrats, as civilian institutions, weakened by repeated military interventions and political instability, were unable to challenge their control.

Scholars have described this cyclical pattern as a “praetorian trap,” one in which the military repeatedly intervenes under the guise of stabilizing governance, only to entrench its own authority. Because of the colonial imbalance between military-bureaucratic power and civilian authority, a long-term consequence emerged: a military strong enough to dominate politics and the poor. In strong democratic governments, parties do not have to rely on family networks because they don’t have to worry about frequent coups and disruptions. Military dominance and weak institutions left families as the only stable source of leadership, because family networks were more difficult to dismantle, while democratic institutions were sidelined entirely. Civilian political elites’ patronage-based structures are too weak to sustain power without military backing, so they are willing to tolerate, or even invite, military intervention when it helps them defeat rivals. The executive branch is hence weak, and mutual dependence institutionalizes military authority, ensuring that no civilian leader can govern independently. Prime ministers in Pakistan lack control over national security policy, cannot appoint military leadership without repercussions, and govern within institutions loyal to the military rather than to elected officials.

Meaningful democratic reform in Pakistan must begin by dismantling the military’s structural dominance and curbing the power of entrenched political dynasties. Currently, the military’s legitimacy derives from a combination of national security narratives (especially control over Kashmir), colonial institutional inheritance, and weak civilian governance, among other social and political factors. Strengthening civilian institutions—particularly parliament, the judiciary, and the Election Commission of Pakistan—is essential to prevent the military from manipulating leadership transitions and to ensure that political parties cannot function as hereditary enterprises. Reforms like transparent party financing, internal elections, and stronger protections for judicial independence would help reduce elite capture. Empowering the working class through political education and stronger local communities would give ordinary Pakistanis a stake in democratic governance, reducing their dependence on patronage and increasing civilian political power. Such an approach would allow political leadership to emerge through democratic contestation, allowing leaders like Khan, who came to power through popular support, to survive beyond the limits imposed by family inheritance or military patronage.

Without such reforms, Imran Khan’s imprisonment will not be an exception but part of a recurring pattern in Pakistan’s political system. His rise and subsequent removal illustrate how popular civilian leaders are permitted to govern only within limits set by the military and entrenched elites, regardless of electoral legitimacy. Until civilian institutions are strong enough to operate independently of military influence and dynastic control, Pakistan’s democracy will continue to function as a managed system. Beyond political exclusion, Khan’s imprisonment raises serious human rights concerns. In December 2025, the United Nations Special Rapporteur on torture raised concerns over Imran Khan’s conditions in prison, citing prolonged solitary confinement, restricted access to medical care, and treatment that may amount to cruel or degrading punishment under international law. Subjecting a former prime minister to detention conditions widely criticized by human rights experts, following trials questioned by legal observers, underscores how deeply civilian authority and legal protections have eroded under Pakistan’s managed democratic system.

Until reform occurs, Pakistan’s elections will not reflect the popular vote but rather what elites have decided to purchase.

Anaya Qayyum (BC ’28) studies Anthropology and Human Rights, with an academic focus on international law, politics, and foreign relations between the United States, South Asia, and West Asia. She can be reached at aq2251@barnard.edu.