The Dangers of Meritocracy: New York City’s “Elite Eight” and the Educational Privilege-Laundering Machine

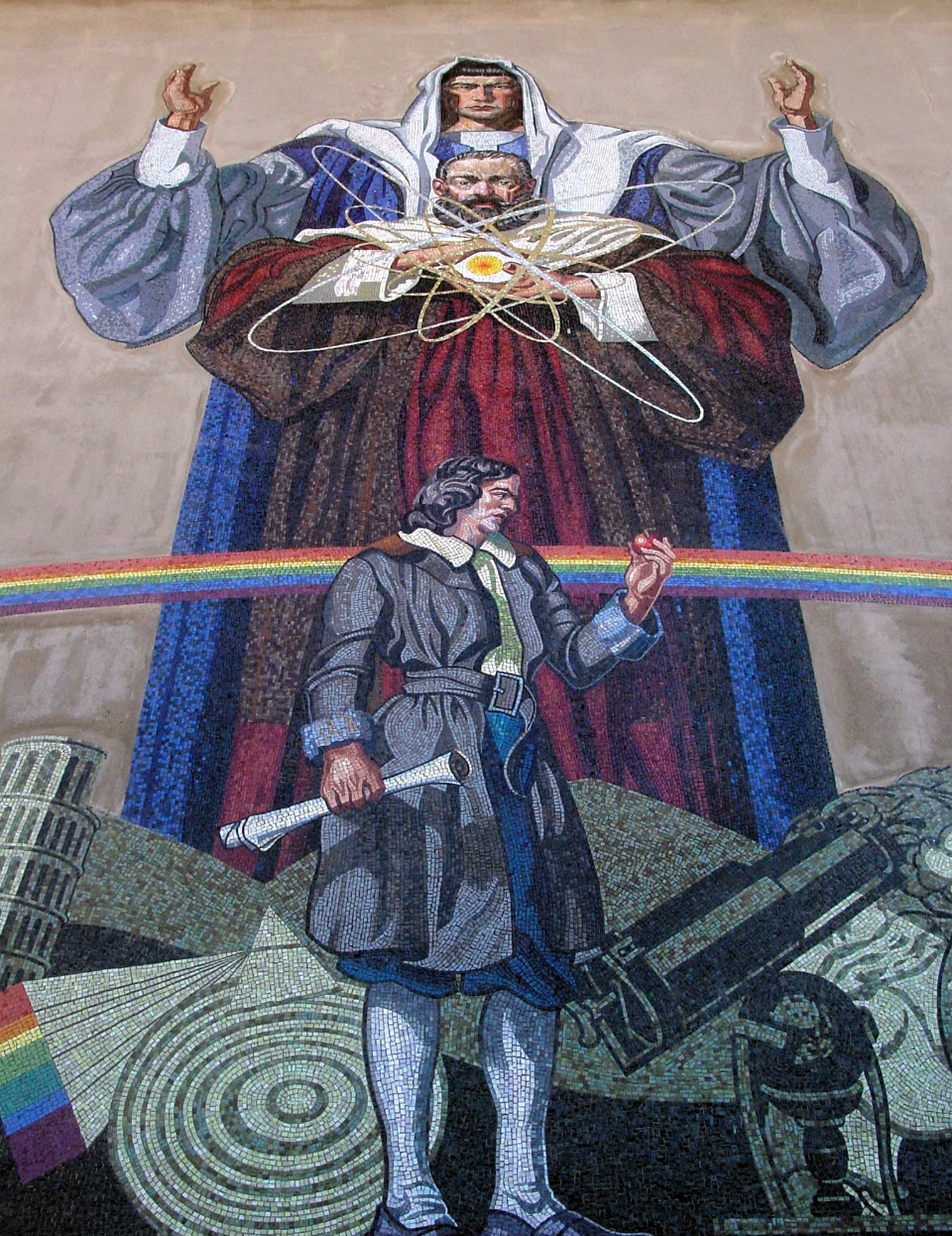

“Humanities Protecting Biology, Physics, Chemistry.” Photo by Neil Degrasse Tyson

A 63-foot Venetian glass mosaic, entitled “Humanities Protecting Biology, Physics, Chemistry,” greets visitors as they enter the Bronx High School of Science. With depictions of Archimedes, Marie Curie, Isaac Newton, and a shirtless Imhotep, the shining implication is that the high school’s nearly 3,000 students will one day rank among these thinkers. The school is one of eight specialized high schools—often called the “elite eight”—which include the Brooklyn Latin School, Brooklyn Technical High School, the High School for Mathematics, Science and Engineering at City College of New York, the High School of American Studies at Lehman College, Queens High School for the Sciences at York College, Staten Island Technical High School, and Stuyvesant High School.

These “crown jewels” of New York’s education system orient their admissions around a single standardized test, which any New York City student can sign up to take for free. The Specialized High School Admissions Test (SHSAT), offered once a year in October, is a student's only gateway to eight schools that produce more Nobel Prize winners than some countries, and boast nearly 100% graduation rates in a city whose graduation rate hovers around the 80% mark. Theoretically, any gifted student can earn a score reflective of their academic potential. Every applicant takes the same multiple-choice exam, in the same hundred-eighty minutes, in the same high school classrooms and gymnasiums. 30,000 students take the exam each year, only 6,000 of whom will be accepted to any specialized high school.

“Standardized” is the key word and the selling point for the utopian ideal of education as the great equalizer. In theory, anybody can excel, armed only with a K-8 education and their wits. In 2012, the city’s then-mayor, Michael R. Bloomberg said that the system boils down to this: “you pass the test, you get the highest score, you get into the school—no matter what your ethnicity, no matter what your economic background is.” So, if meritocracy is so openly centered in admissions, what is being implied about the students who don’t make the cut—especially when these schools consistently under-admit Black and Hispanic students? Are we supposed to accept that in 2020, only 24 Black students were admitted into Bronx Science’s freshman class of 750 (up from 12 the year before) because the students that make up the city’s demographic majority just couldn’t hack it? When such symbolically important institutions are so inaccessible to the city’s majority, the definition of excellence narrows until it can only accommodate those with money, time, and access.

From the mid 1970’s to the early 1980’s, the “elite eight,” using the exact same criteria for admissions, became an academic haven for low-income students of color. In 1976, Stuyvesant, the most selective of the eight, had a population of nearly 15% Black and Hispanic students. But, by 2014, the school accepted only seven Black students and 21 Hispanic students, making up just around 3% of the freshman class of 952. This is not a reflection of the city’s diversity overall—70% of students in New York City’s public schools are Black and Hispanic. So who, if not the underrepresented majority, are these schools meant for? The admissions system of Specialized High Schools tends to privilege White and Asian students coming from accelerated feeder middle schools, who can afford extensive test preparation and have parents with the time and fluency in English to guide them through the process. Basically, the people with all the systemic support they could possibly need. The allegedly meritocratic admissions system is nothing more than a privilege-laundering machine, which, by some statistical accident, briefly served the people who needed it most.

There may not have been any intentional effort to freeze out Black and Hispanic students, but there was certainly no effort made to bridge the demographic gap. In 2012, the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, along with a number of influential civil rights groups, brought a complaint against the federal Department of Education alleging that the SHSAT discriminates illegally against Black and Hispanic students. The complaint specifically cites Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which requires that “no person in the United States shall, on the ground of race, color, or national origin, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any program or activity receiving Federal financial assistance.” Students of color, the complaint asserts, are unfairly discriminated against by such a complete reliance upon the SHSAT.

It is also worth noting (though it is not explicitly mentioned in complaint) that the test preparation industry in New York City has more than doubled in the past fifteen or so years, and rigorous test preparation, either through group courses or private tutors, has become the norm for specialized high school applicants. If a student wants to earn a standout score, it is essentially required that they shell out at least $20 for practice tests and answer keys, or $1,000+ for a group in-person course. Beyond the money issue, there exists a further barrier to accessibility for students of color: the Bronx, the borough with the highest concentration of Black and Hispanic students, is also the borough with the fewest test prep centers, with only thirteen total compared to Manhattan's 158. Because test prep centers are so few and far-between, the majority of students in the Bronx would have to dedicate a great deal of time to an extended commute. It may seem unimportant, but even an hour of back-and-forth on the subway can be draining, and poses an additional disadvantage to already-disadvantaged students.

In order to move forward from an “unjustified, and singular reliance on the SHSAT,” the complaint suggests a high school admissions process that closely resembles the American college admissions process, with weight placed on qualities like middle school GPA, letters of recommendation, attendance records, and leadership positions. In 2013, former mayor Bill de Blasio’s administration pushed legislation articulating those same desires, in addition to a program, called the Discovery Program, to admit low-income students whose SHSAT scores put them just below the cutoff. While the Discovery Program succeeded—by the end of 2020, 20% of seats at each specialized high school were reserved for Discovery Program participants—the dream of holistic admissions was never realized.

Even if qualities like attendance and GPA were to be weighted as they are in college admissions, not all middle schools are created equal. For one, only nine middle schools in the Bronx have gifted and talented programs, while a single high-income district in Manhattan has eight gifted and talented programs, which enroll nearly 2,000 students. New York state’s public school system is the most segregated in the country, and the illusion of meritocracy is not enough to fix deeper issues of educational inequity. Some middle schools do not even tell their students about specialized high schools or SHSAT. And the students at these schools are left behind in the race to graduate, to get into college, and to find fulfilling careers, all before they turn fifteen.

Effectively leveling the playing field seems an elusive goal—even a college-style admissions process would remain deeply flawed. Still, it is important that the city’s legislators try to interrogate the system and make change, however marginal it may seem. To treat the SHSAT as an objective measure of intelligence is to treat racial disparities in specialized high schools as the result of an inherent inferiority. Following the exam’s internal logic to its conclusion, one might ask, are White and Asian students just smarter than others? If not, then what is being implied?

Rebecca Kopelman (BC ‘25) is a staff writer with CPR studying English and Philosophy.