Law and Order: Perpetuating Mass Incarceration Under the Guise of Safety

The U.S. unequivocally uses the prison system for profit rather than reform. America has the highest rate of incarceration in the world—disproportional to our population—and currently allows that system to function as a modern means of systemic oppression. Law and order rhetoric—which emphasizes ‘cleaning up the streets’, protecting youth from succumbing to drug use, and reducing violence— almost always has racist undertones that persecute the existence of Black individuals, particularly low income Black individuals. This, in conjunction with tough on crime mentalities, have allowed racist and ineffective policies to become the norm. As a result, America’s structure of mass incarceration, entrenched in racism, is not going anywhere without concerted changes in policy and rhetoric. We need to listen to advocacy groups that have been paying attention to injustices far longer than politicians who have only recently stopped pushing for the same “law and order” that Trump weaponized as a means to criminalize BLM advocates and fear-monger his way into a second term. The people who spout “this [referring to any of the numerous crises we confront] is not America'' must reckon with the fact that the country may not embody one’s ideals of a modern America, but that it is our reality nonetheless. Historic and explicit racism has become increasingly covert but persistently salient to a myriad of American institutions, mass incarceration being one of the most insidious.

Our history allows us to understand how we arrived at the tangled state of affairs, but more importantly, it allows us to begin to create policy that no longer perpetuates racism under the guise of safety. Although Jim Crow laws— the codified segregation and oppression of Black people after the Emancipation Proclamation—no longer exist overtly, their impact can be observed in the advantage white people have in access to resources, jobs, and property. This connects to another means of marginalization in the grim timeline of systemic racism: the War on Drugs. Beginning in the 1970s with President Nixon—another candidate who ran on law and order rhetoric— and evolving to this day, the War on Drugs furthered policies that mandated harsh sentences and propagated fear around drug use. Police would frequently patrol neighborhoods with high Black populations, stopping as many people as possible. Consequently, the United States now leads all other nations in incarcerated people, with 2.3 million people behind bars. While it is currently the Republican Party who is most known for harkening law and order, Democrats have feared retribution in the past for the reputation of being too soft on crime, and in 1986 pushed through a bill requiring mandatory minimum sentences for drug offenses in order to appear “anti-drug.” In 1988, then-Democratic presidential candidate Michael Dukakis was campaigned against for being soft on crime, begetting white fear that Democrats would release “dangerous criminals.” These bigoted and unfounded fears bully politicians into passing certain legislation and taking entire party-stances that disproportionally impact people of color.

The fact that Black people have the highest rate of incarceration (more than quintuple that of white people) is not a curious accident to shrug your shoulders at. Rather, it is manufactured to be this way through practices such as the ’94 Crime Bill, the origin of policing, the lack of resources for less affluent communities, and the damaging verbiage that politicians have employed to be elected. The deck is stacked against those that were not born with a silver spoon, which is why we must undo the way incarceration was manufactured. At every step—arrest, trial, serving, probation—racial disparities are visible. Prosecutors are twice as likely to press for mandatory minimums with Black defendants, and those same defendants are then less likely to receive relief from those minimums. Furthermore, a Black person convicted of a drug offense serves the same average time as a white person convicted of a violent crime. If “law and order” had any grounds to stand on, this one statistic should be enough to crumble them.

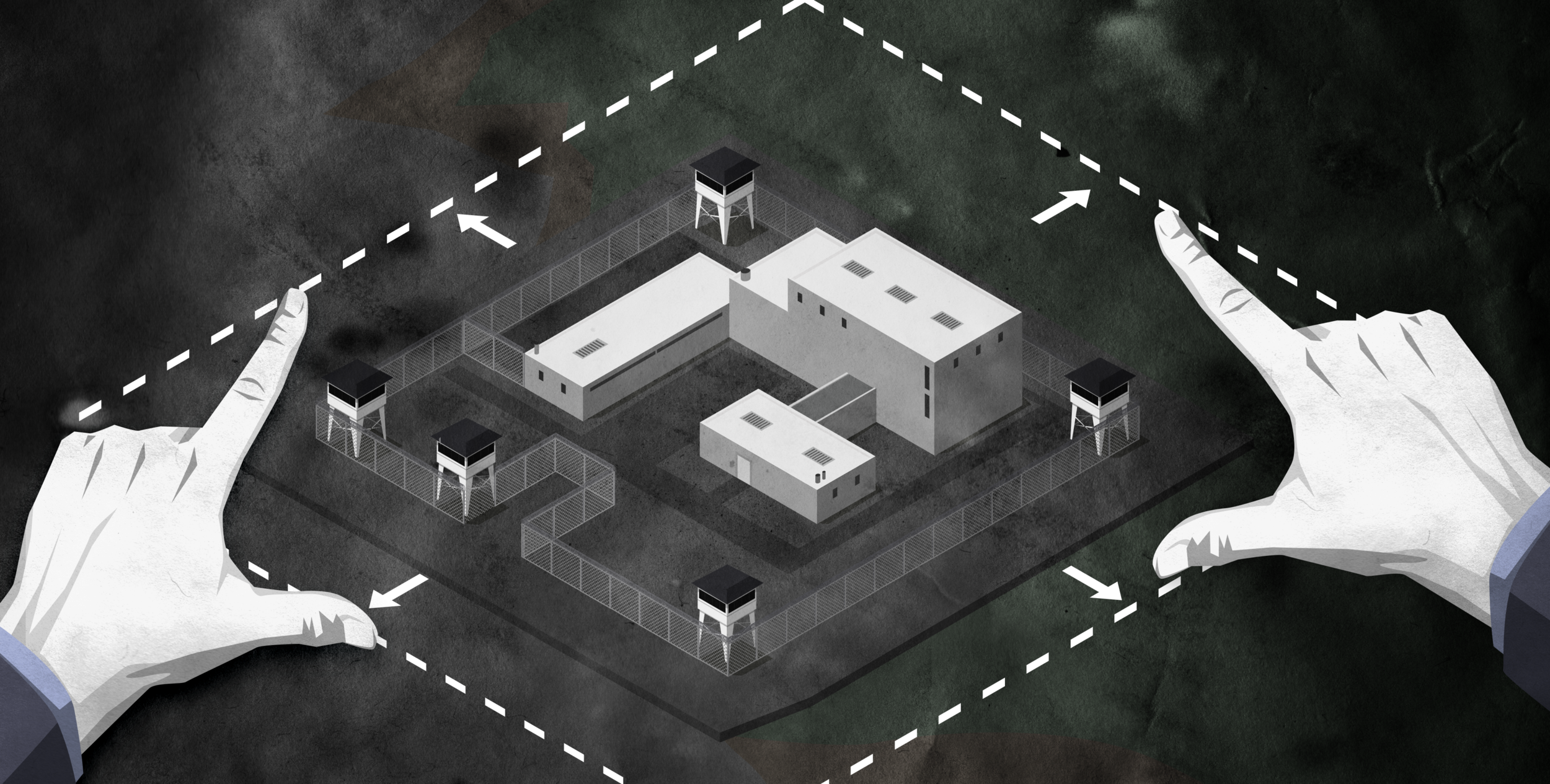

A depiction of the man-made nature of mass-incarceration. Photo by Jared Rodriguez.

No matter how difficult it is to conceptualize 2.3 million incarcerated people, it should be easier to recognize that it is egregiously disproportionate to the crime rate in America. The U.S., with only 5% of the world’s population, holds a quarter of imprisoned individuals, and since the 1990s, has increased spending on corrections from 16.9 billion to 60.9 billion. This should be alarming considering that violent and property crime rates have plunged since the ’90s. Although it certainly doesn’t help, Trump’s cries for “law and order” are not the sole cause of the trends we’ve seen for two decades. This begs the question of how things have gotten so bad right under our noses. The short answer? Profit.

The most obvious source of profit is privatized prisons, but they make up a small piece of the larger puzzle, contributing only marginally to profit found in incarceration. President Biden “banned” private prisons on January 26, essentially phasing them out, and there is already plenty of criticism that this move was not enough. Less than 9% of incarcerated individuals are kept in private prisons, which are largely made successful from the greater system of which they are a part. Prison labor makes incarceration profitable to corporations as well as the prison itself, and although the 13th Amendment abolished slavery and involutary servitude, Section 1 also says “except as punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.” Racial disparity in prisons has led prison labor to look a lot like modern day slavery under the guise of law and order.

Policies attempting to slow the expansion of the prison industrial complex are beginning to gain traction as the issue of mass incarceration grows in urgency and public opinion. In 2019, Senators Bloomenthal, Booker, and Representative Cárdenas introduced the Reverse Mass Incarceration Act (RMIA) to combat the incentivized system of increasing prison populations. Such legislation would have $20 billion in federal funds to provide to states over ten years that decrease their prison population by 7% over three years without an increase in crime. This money would have to be invested in further reducing incarceration and crime. Senator Cory Booker acknowledged that “incarceration tears families apart, costs us billions annually, and doesn’t make our communities any safer.” This comes more than two and a half decades after the 1994 crime bill, which in part drove the increase in incarceration since the ’90s. President Biden authored the ’94 crime bill, and now supports the RMIA, an important evolution of policy and important to its potential future in the coming months post-inauguration. The RMIA legislation is based on a 2015 proposal by the Brennan Center for Justice at NYU Law, which also asserts the importance of providing federal grants for reducing prison populations. Money speaks, and by drying up monetary support for being “tough on crime,” we can discontinue the blind acceptance of mass incarceration. We can also begin to propagate the belief that the prison system is cyclical and disenfranchises rather than rehabilitates which would encourage investment in housing, education, and after-school programs. These are all concrete ways we can pull people out of—and protect them from falling victim in the first place—our corrupt incarceration system.

Federal policies and legislation are vital, but state-level reform serves as an example to the rest of the country. In Michigan, Governor Gretchen Whitmer signed a “Clean Slate” criminal justice reform bill on January 4, with multiple opportunities for current and formerly incarcerated individuals. This bill has made it easier to have records expunged, a step to decrease felony disenfranchisement that hinders anyone with a record from getting a job, voting, and creating a life for themselves beyond bars. Additionally, this legislation will abolish mandatory minimum sentences, reduce penalties for multiple low-level offenses, and seal the records of juvenile offenders. Governor Whitmer hopes these initiatives will reduce poverty and stimulate the economy, with research from the University of Michigan finding that people who receive expungements see a 23% salary increase within a year. Meek Mill and Jay-Z’s criminal justice reform organization—REFORM Alliance— advocated for these laws on the behalf of Michiganders and millions of people both incarcerated and under the control of probation and parole officers. Under the RMIA, state-based initiatives such as these that decrease prison populations would be eligible for federal funds, which tackles the majority of prisoners that are not incarcerated in private prisons.

With the recent Senate wins of Reverend Raphael Warnock and Jon Ossoff, Democrats have majority control of both the executive branch and Congress, providing the opportunity to pass sweeping—and categorically necessary—prison policy. This could start with the RMIA, but should be parallel with more bottom-up approaches such as legalizing marijuana and expunging prior convictions for recreational use, negating some of the detriment that the War on Drugs has proliferated. President Biden’s vision for justice includes the decriminalization of cannabis, but says it is in the states’ hands to legalize recreational use, preserving the nationwide discrepancy of sentencing for marijuana-based offenses. An estimated 40,000 people in jail for marijuana are watching legalization proliferate as they continue to serve. In a period of time when media is incessant and catastrophe is unrelenting, there seems to be not enough bandwidth or hours in the day to speak out and act for reform across the board. As millennials and Gen-Z emphasize the perilous nature of global warming, call for the defunding of police, and assert the crushing amount of student debt, addressing mass incarceration needs to be in that same breath.

Just because a problem is not easily solved with one bill or executive order does not mean we should stand still and allow the issue to metastasize. In actuality, it is these exact issues that must be given the most attention, in order to capitalize on democratic majorities early on and not let the clock run out as people suffer. How broken is a system of arrest that 326 people were arrested on June 1 alone for BLM protest and only 230 arrested so far in the storming of our nation’s capitol on January 6? Democracy is fragile right now in the United States—conflict gets louder by the second and divides seem to be etched in stone. This is precisely why we cannot waste more time staying silent. A nation heals when you start from the roots and allow yourself to look at the ugliness you’ve dug out, not just put band-aid after band-aid on whatever crisis pops up on the daily. We cannot count on institutions to evolve for the better when they are doing exactly what they were created to do: perpetuate the oppression of marginalized individuals. This calls for changes introduced in the legislature, beyond even federal funding for decreasing prison populations or making it easier to have a record expunged. Words carry weight, and we desperately need to retire rhetoric surrounding law and order, which is convincing citizens of a false reality with a false solution.

Olivia Deming is a Staff Writer at CPR and a first-year student in Columbia College studying Political Science with a focus on International Relations. Originally from Michigan, she is enjoying exploring the city and growing roots in her new home.