In the Time of COVID-19, Your Right to Vote Has Never Been More of a Privilege

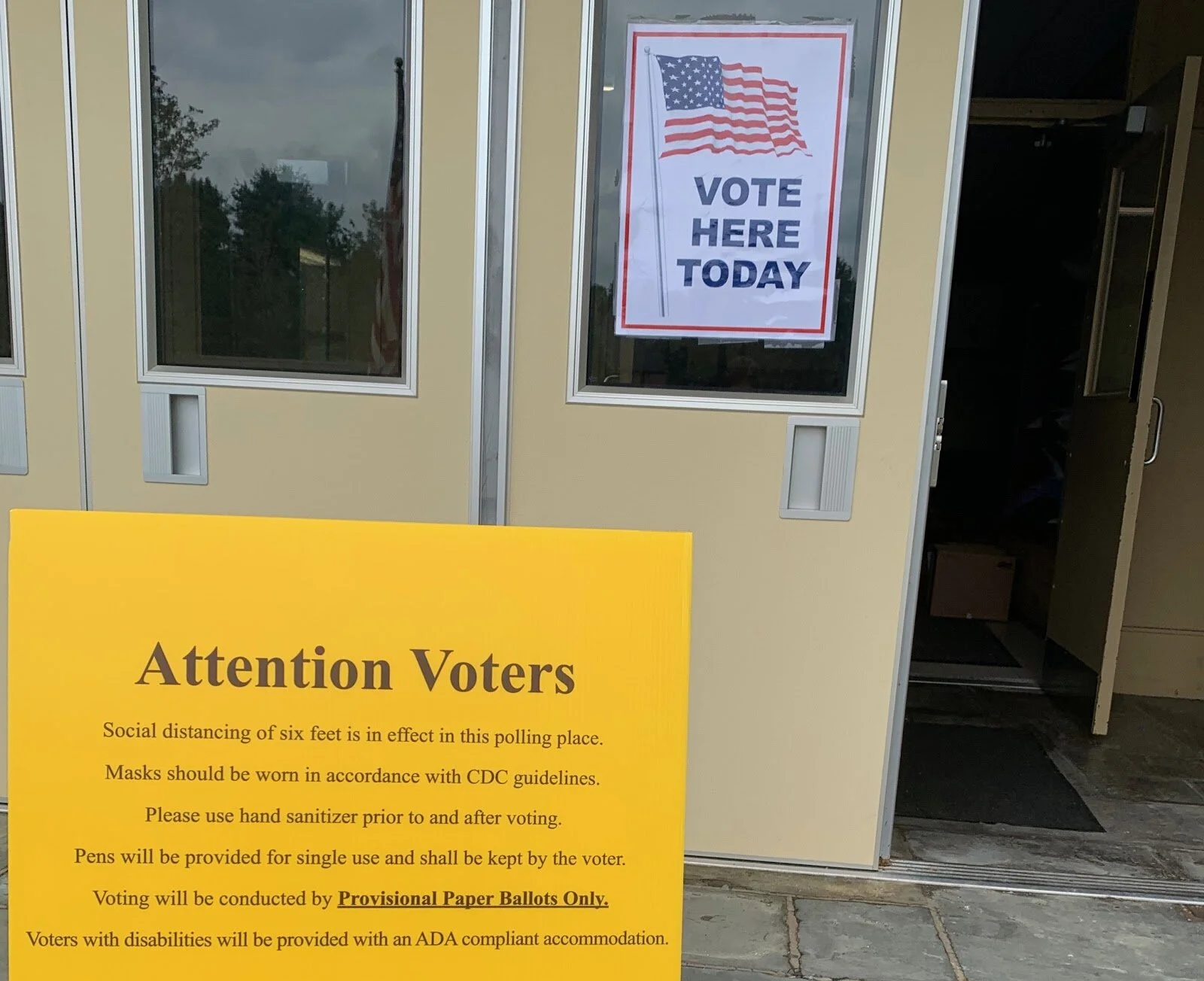

The voting station in Chatham, New Jersey where the author cast her provisional ballot after her absentee ballot failed to arrive. Photo provided by the author.

As a New Jersey resident, I have always found it relatively easy to vote. When I entered Barnard, I filled out an absentee ballot request form. I checked the box to have an absentee ballot sent to my school address in New York City for all future elections. It seemed like a good idea at the time.

When I heard New Jersey’s July primary was going to be conducted primarily through vote-by-mail, I was happy. I could vote from the safety of my home without endangering my high-risk family members. I sent in a new absentee ballot request to make sure my ballot was sent to my home address. I even spoke on the phone with someone in the registrar’s office in my county to make sure everything was in order. I kept seeing pictures on social media of the special ballot lock boxes being used in this election. This looked like a great development for our democracy. July 7th came and went—and my ballot never arrived. I started to rethink the efficacy of vote-by-mail systems.

During college, I spent a lot of time studying forms of voter suppression and now know that there are numerous reasons why one might lose access to their right to vote.

Since the gutting of the Voting Rights Act in the 2013 Supreme Court case Shelby County v. Holder, systems of voter purging have proliferated. Improper purges, based on either bad methods or bad information, took place in New York and Virginia in 2016, and in Georgia in 2018.

Additionally, those with prior felony convictions can permanently lose their right to vote in many states. The Supreme Court recently upheld a Florida law that requires otherwise eligible voters with a felony conviction to essentially pay a modern day poll tax to restore their right to vote.

Strict voter ID laws, long lines, and numerous other forms of voter suppression persist in this country. A lost ballot, in comparison, does not seem like a big deal. I consider myself lucky to be in the position I am when drawing comparisons between my voting experience and others’. If you continuously keep the disenfranchised in mind, you will begin thinking of your ability to vote as more of a privilege than a right.

Widespread disenfranchisement has always been a part of this country’s history. However, the unique challenges of this pandemic may lead to many more obstacles getting in the way of individual voting rights.

My mail-in ballot woes began when N.J. Governor Phil Murphy issued an executive order to make the July 7th primary a primarily vote-by-mail election on May 15th. Was less than two months enough time for county registrars to deliver huge quantities of mail-in ballots to voters? Maybe not.

As we hit another surge in coronavirus cases, states may make decisions about transitioning to mail-in ballot systems for the upcoming November elections, like what New Jersey did in the July primary.

Moving to a primarily vote-by-mail system is the right thing to do from a public health standpoint, but there are drawbacks. One big problem is that someone’s voter registration address might not be the same as their mailing address. College students are especially prone to falling into this trap, so fill out your absentee ballot requests early.

Mail-in voting actually has huge potential for improving the voter experience when done correctly. The Brennan Center for Justice reports that there is no evidence of significant fraud tied to voting by mail. Five states currently conduct all elections by mail. States like Washington and Utah reported improved voter turnout after instituting automatic vote-by-mail systems.

But making automatic vote-by-mail work requires changes to election office operations that cannot be implemented in a matter of months. For example, voting rights experts recommend printing enough ballots and envelopes to cover 120 percent of the number of registered voters in a district—a huge ask for districts used to in-person voting.

It is also recommended that public education specialists be employed to educate voters about changes to voting rules and options. After Hawaii transitioned to an all-mail voting system, Honolulu county had to significantly increase support services for voters, while also investing more time in maintaining voter rolls. These staffing changes may be impossible for many districts to implement in just a few months.

States that did not implement universal vote-by-mail in the recent primaries struggled to keep up with an increased demand for absentee ballots. Counties have reported printing and budgetary issues. Mailing ballots can drive up costs, and money currently allotted for election expenses is not enough. These were issues in states that did not mail ballots to every registered voter. This does not bode well for November.

The five states with permanent, universal vote-by-mail in place demonstrate how these systems take years to perfect. In Oregon, mail-in voting was tested in local elections beginning in the 1980’s. It was then experimented with in a state special election before Oregon residents voted on a ballot measure to implement mail-in voting in all future elections in 1998. Oregon voters were able to decide if vote-by-mail was right for them. This year, we do not have the same choice.

The issue is not with universal vote-by-mail, but with how voters will be disenfranchised by not getting a ballot in the mail at all when the system is hastily implemented.

Currently, one can be disenfranchised because of a clerical error, or because a registrar’s office was understaffed and overwhelmed. This is what I believe happened to me in the New Jersey primary. Administrative hiccups are not new, but issues tied to the pandemic will only further disenfranchise.

I was able to cast a provisional ballot in the New Jersey primary. After multiple calls to the board of elections, I was able to finally verify my vote was counted three weeks after the election took place. Potentially losing my right to vote in this way was eye-opening. Watching my mom and sister fill out their absentee ballots at home, I felt as though they had a type of privilege I had been denied.

If you happen to both live in a state that institutes vote-by-mail to keep you safe, and you receive a ballot that you can reasonably use prior to election day, you have privilege. You also have privilege if you feel safe enough to go vote in person, if polling places are not overcrowded, lines remain relatively short, and social distancing is maintained.

I was able to walk to a near-by school to cast my provisional ballot. The polling place was almost empty, everyone was wearing a mask, and I had no trouble obtaining a ballot from the poll workers. Though having to go vote in person was an annoyance given the context of my situation, having an in-person voting experience like mine has been a rarity in some parts of the country—even before the pandemic.

We are all beneficiaries of privileges we can leverage to uplift others. If you have a ballot you can use, leverage it. If you don’t feel enthusiastic about this election, think about someone who might want to participate but can’t. Apathy is the only byproduct of privilege that can’t be leveraged for good.

If you think voting should be a right and not a privilege, then you should feel energized by this election. Your participation in this election can affect the enfranchisement of other Americans by impacting the future of Congressional legislation. The House has passed bills to reform elections and restore the Voting Rights Act. Neither of these have been brought to a vote in the Senate, and the executive branch is against these bills becoming law. If the balance of power in the Senate were to shift, it becomes more likely that voter protections will be expanded. A fully functional Voting Rights Act would allow the Justice Department to oversee changes states and districts make to election policy—oversight which has not been in effect since the Supreme Court’s Shelby County ruling in 2013.

Your vote also determines who your state and local officials are. These are the people who actually make and implement changes to election policy. Gubernatorial and state legislature elections matter. And if you live in one of the twenty-four states with an elected secretary of state serving as chief election official, then secretary elections matter too. Many states, like New Jersey, also have elected county clerks that manage elections for individual counties.

As a voter, you have the power to decide who is making changes to election policies that affect every level of government. Do you support automatic voter registration, no-excuse absentee voting, restoring voting rights to those who have completed felony sentences, and the numerous other ways voting rights can be expanded? By casting ballots for officials in upcoming elections, you express what you want elections to look like in the future.

Your choice to use your voting privilege can determine who has access to votes they should already have in coming elections. Your voice can amplify others’.

While vote-by-mail may be an imperfect answer, it is the best one we have. To make sure it works as well as possible, check your registration and check it sooner rather than later. Request an absentee ballot now if you can, or as soon as you know where you will be living on election day. Tell your friends to do all of this too. Keep an eye on your state’s policies, because things will change. Be proactive. This vigilance will be necessary to ensure voters’ and poll-workers’ safety if in-person voting takes place, and for adapting to the logistical challenges of mail-in voting. If and when you get that ballot, use it for those who didn’t get one. Speak for those who can’t.

Olivia Roche graduated from Barnard in May 2020 with a major in Political Science. She is spending her summer living directly in front of her middle school in New Jersey while trying to combat voter suppression with Students for Justice- A Reclaim Our Vote Initiative. Though she claims she is “not like other girls” who study Poli-Sci, she will be moving to D.C. to start Georgetown Law in the fall.

This article was submitted to CPR as a pitch. To write a response, or to submit a pitch of your own, we invite you to use the pitch form on our website.