The Road Forward for Afghanistan

On August 21, 2017, President Trump announced his administration’s long awaited policy towards South Asia, particularly Afghanistan. As a part of the new policy, the United States will remain inside the war-torn country indefinitely and so will continue the longest conflict in American history.

If you ask most Americans why we are in Afghanistan, they will answer something along the lines of: to fight Al-Qaeda or to end terrorism. After all, those are the stated goals of the Pentagon and were legitimate reasons for going to war following the horrific attacks on September 11, 2001. However, after sixteen years of bloodshed, with thousands of lives lost on both sides, the core issue remains: Why are we still in Afghanistan and what have we achieved up to this point?

During the 2016 election, politicians from both major parties barely acknowledged the conflict. As early as 2009, President Obama vowed to end the war, but he instead escalated the effort by deploying more troops. President Trump, although initially opposed to the war, has announced his intention to continue with no end in sight. In fact, during his first formal address about this issue, he promulgated: “My original instinct was to pull out—and, historically, I like following my instincts. But all my life I've heard that decisions are much different when you sit behind the desk in the Oval Office; in other words, when you're President of the United States.” This trend, of switching from using peaceful rhetoric during campaigning to choosing a continuation of war policies when in office, is nothing new. For example, the same occurred under the policies of former Secretary of State Henry Kissinger during the Vietnam War and in countless other examples. However, in contrast to the case of Vietnam, the media coverage on Afghanistan has been severely lacking, to an appalling degree. Moreover, politicians’ refusal to address the issue while still continuing the war effort has caused most Americans to remain unaware of the immense monetary and humanitarian costs of the war. As a result, since the mid-2000s, Afghanistan has become a background issue in the wider arena of American domestic politics.

So what are the actual costs of the war? In numbers: over $1 trillion has been spent since it began, more than 22,000 American coalition members have been injured or killed, upwards of 173,000 Afghans and Pakistanis have suffered fatalities (the majority civilians), and, just this year, there has been a 25 percent increase in the number of children who have been wounded or perished. All of this excludes the immense economic and infrastructural damage that Afghanistan and surrounding countries have incurred. Given all of this information, one must wonder: What have we achieved during the conflict?

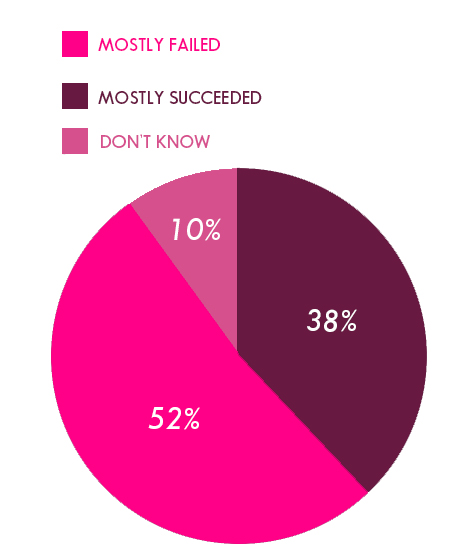

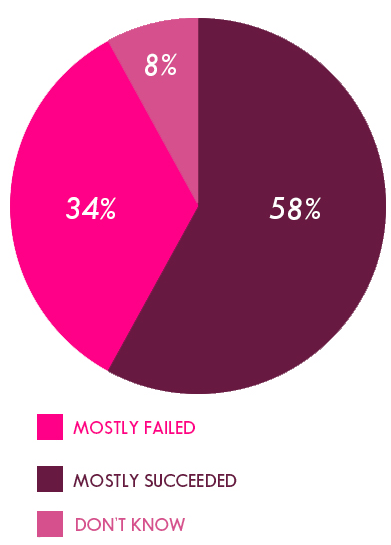

PEW RESEARCH CENTER / USA TODAY

Unfortunately, not much. In 2011, American deployments reached a peak of 100,000 troops. Because troop levels started falling shortly afterwards as part of an initial withdrawal policy, the Taliban have been resurging in immense numbers. They have secured control of over 40 percent of the nation’s districts and continue to challenge the Afghan National Security Forces and the American military. Members of the International Security Assistance Force (ISAF), a coalition of countries that aid American war efforts, have also shown a reluctance to carry on with the war. Furthermore, the United States is facing major diplomatic setbacks, as regional powers have been attempting to exert their own influence in the strategically located country. Russia, Iran, Pakistan, China, Qatar, and to some extent Turkey have all been engaging with the Taliban in an effort to reach a peaceful resolution to the war—independent of the United States. These factors, in turn, may entangle America in even more complex diplomatic issues. In addition, greater involvement by surrounding nations implies that other powers do not see the American campaign as a successful one and are instead moving to assert their own influence in Afghanistan.

Despite the changing geopolitical interests in regards to other countries’ movements in Afghanistan, there is no doubt that the United States will need the cooperation of the most powerful regional players if it is ever to broker a resolution to the conflict. During the Soviet-Afghan War that lasted from the late 1970s through the 1980s—and referred to as the Soviet’s Vietnam by historians for its devastating failure—Pakistan was instrumental in helping the CIA bring down the USSR in the country. In 2001, President Bush approached Pakistan to request assistance for transporting soldiers and supplies through Pakistani soil to landlocked Afghanistan. Regardless of the precarious diplomatic relationship between the two nations since then, it is evident that Pakistan is one of the most influential players in this conflict and will be a vital ally if the United States is to succeed. President Trump’s decision to attempt circumventing Pakistan in his new policy and to involve countries that have no prior experience in Afghanistan may only obstruct the long term goals for regional stability. In a panel with the Council on Foreign Relations on September 20th of this year, Prime Minister Shahid Khaqan Abbasi of Pakistan mentioned that, “We have engaged with the US. We continue to engage with them to resolve any differences that come up and move forward.” It may thus be in the best interests of both sides to work together and cooperate on the issues plaguing Afghanistan.

Given the declining trend in American effectiveness in Afghanistan, we are left to evaluate whether more troops will actually do anything to affect the outcome of the war. The Pentagon makes a valid argument when it warns that the logistical and military failures in Iraq, where the premature removal of troops opened a dangerous power vacuum in that country, might be repeated. Similarly, many argue that it would prove devastating to end the war effort in Afghanistan right now, as it might allow some other group, like the Taliban, to once again regain control. Therefore, President Trump’s announcement to send 4,000 troops, in addition to the 8,400 already on the ground, ostensibly seems like the wise thing to do.

In reality, however, the president’s decision does not differ much from those of his predecessors, and many analysts claim that the new policy will be futile in its efforts. If the Taliban have not capitulated yet and instead continue to flourish in the country, more troops being deployed may actually backfire in the end. The Taliban will be able to recruit more members for their cause under the banner of “protecting against an occupying power,” as they perceive it. The introduction of more troops will only inflame extant anti-American fervor and could even be misused to fuel the growth of the terrorist organization. Given that in 2011 there were upwards of 100,000 troops stationed in Afghanistan, it is difficult to see what effect just a fraction of that total will now have on the outcome of the war. For its part, the central government in Afghanistan has failed to tackle vital problems, such as inadequate security organization and government corruption, which itself hampers American efforts. Furthermore, as mentioned earlier, the growing presence of other nations in the conflict only exacerbates the situation and makes it more difficult for troops to battle the terrorists efficiently . This, in turn, has prompted criticism from some politicians, such as when Senator Rand Paul (R-Kentucky) asserted, “The mission in Afghanistan has lost its purpose, and I think it is a terrible idea to send any more troops into that war.”

President Trump also proclaimed in his speech that, “We are not nation-building again. We are killing terrorists.” This rhetoric of explicit restraint in helping Afghanistan rebuild could be disastrous in the future. One of the primary reasons that ISIS was able to rise to prominence in Iraq after the American withdrawal was due to the lack of a coherent post-war plan for the country. The decimated infrastructure and deficient bureaucracy meant a weak, decentralized state that was unable to maintain unity. If America hopes to see some success in its fight against Afghani insurgents, it is imperative that this nation help rebuild the country. Reflecting on history, the Allied powers assigned an inordinate and unrealistic amount of debt to Germany following World War I. The economic pressure eventually allowed Hitler to take advantage of debilitated government institutions and to seize control—and we all know what happened next. After World War II, however, the Marshall Plan allocated vast funds to Japan and Germany, both of which were primary enemies during the conflict, eventually allowing them to rebuild and preventing fascist and radical forces from once again rising. Today, both of those countries are close allies of the United States and boast robust economies. History teaches us that we must do the same in Afghanistan if we are to maintain the legacy of those who valiantly lost their lives in the war effort.

Conventional warfare does not seem the path to success at this point. Rather, the United States must wage a war of ideology through education. Every war is won through the hearts of the common people and, right now, many Afghan civilians do not clearly understand America’s goals in their country. If the people of Afghanistan do not know what we are fighting for, then our efforts will ultimately be useless. It is also imperative that American generals and the federal government take into consideration the cultural differences that exist in the deeply conservative country. Using religion and culture to paint an image of America’s goals will be essential to both preventing the growth of the Taliban and to potentially changing it from within. Furthermore, it seems counterintuitive for President Trump’s administration to abolish the special envoy to Afghanistan-Pakistan. Instead, the administration should expand efforts to research the future of the region and engage in cultural dialogue.

Every alternative solution to continuing the War in Afghanistan requires involving all current players in the country and greater region. Instead of escalating the conflict, the United States should look at other factors that could reduce costs, in all its forms, for both civilians and militaries. First, the United States should try to rein in government and security corruption in Afghanistan and should eventually transfer control to a better trained and more adept version of the Afghan Security Forces. Second, America should continue diplomatic outreach to major foreign powers that have both cultural and political footholds in Afghanistan in order to initiate a war of ideology. This ideological warfare can only be achieved if more funding is provided for education. Finally, the United States should help to rebuild Afghanistan’s institutions and provide jobs and better communication networks for the remainder of the population. This will feed economic growth and encourage people to turn away from the Taliban, to look towards the positive future that peace can bring. In turn, this could give America much more political leverage, as the Taliban would be reluctant to attack development projects, a move which would cause more civilians to turn against them.

Afghanistan has been in a perpetual state of conflict for centuries, with all of the world’s greatest powers involved at one point or another. It has also been the site of longest running war in which the United States has been entangled, and it is thus necessary to step back for a moment and reflect on the role that we, as citizens and upcoming policymakers, have played in the war in Afghanistan and how we should proceed in the future.

Shayan Rauf is a student at Columbia College studying Economics-Political Science. He is passionate about foreign affairs and economic policy especially in areas concerning the Middle East and Asia. In addition to the Political Review, Shayan is a contributor to other prestigious publications like Encyclopædia Britannica. He can be reached via email at sr3460@columbia.edu.