Switzerland’s Holes: An Undecided Population in a Far Right Climate

On February 9th, 2014, Switzerland passed the popular initiative “against mass immigration,” an initiative that has compromised Switzerland’s international position and relationship with the European Union to the point where EU Commissioner Lazlo Andor stated in a press release that “Business [with Switzerland] as usual is not an option.” What led him to use such harsh terms? The referendum, which was first blocked by the National Council with 140 votes against, 54 in favor and 1 abstention, addresses the issue of immigration in Switzerland. It seeks an independent national immigration policy and the right to impose quotas on immigrants, foreign residents, and foreign workers. Furthermore, it asks that all existing international treaties be changed to implement the terms of the referendum. What it fails to acknowledge is that it clashes directly with the bilateral agreements Switzerland has with the EU, particularly the policy of freedom of movement for workers. This freedom allows workers in EU states and a few others (such as Switzerland) to find work in other member states without being subjected to discrimination based on nationality and the burden of international working permits. One can see how valuable this rule is, especially for Switzerland because 80 percent of its trade is with EU member states. Nonetheless, the referendum passed with 50.3 percent of the vote and will be implemented by 2017. This is not the first time Switzerland has acted so harshly on the topic of immigration. In 1970 James Schwartzenbach, a right-wing Swiss politician, initiated a referendum on Überfremdung (excess of foreigners) as a reaction to the influx of Italian workers after World War II. He proposed limiting foreign workers to a tenth of the total working population, which would have entailed the deportation of almost 300,000 foreign workers over 4 years. The referendum was blocked by 54 percent of the vote after a record 75 percent voter turnout. It is interesting to see that this fear of immigration has remained embedded in the Swiss mentality, especially in cantons located near the borders (which have the most foreign workers) and those outside economic and political centers where there is very little diversity in the population. In the case of Italian foreign workers working in the Italian-speaking part of Switzerland (mostly in the canton of Ticino), who currently make up over fifteen percent of a local population of 350,000, it comes as little surprise that the Italian canton had the most favorable votes for the referendum, with around 68 percent in favor. Xenophobia is being cultivated in these regions, especially since the number of foreign workers in Ticino has nearly doubled in the past 10 years. But the unemployment rate has remained basically constant in the region over this same period, which means that the economy is growing and new jobs are being created. The main hubs of the disinformation suggesting economic pitfalls of immigration are the far-right parties, such as the Swiss People’s Party (also called Schweizerische Volkspartei or SVP), which capitalizes on the fears of the Swiss people and uses them to its advantage. For example, SVP heavily criticized the migrant crisis, with the demagogic result of higher representation in parliament after the 2015 elections. They also initiated another referendum to deprive refugees of free legal representation. This party is not only currently the majority in parliament, but is also the largest majority in Swiss history. To further understand the party’s political stance, one can observe its posters during past elections depicting immigrants as rapists, black sheep being kicked out, and crows eating out of Switzerland.

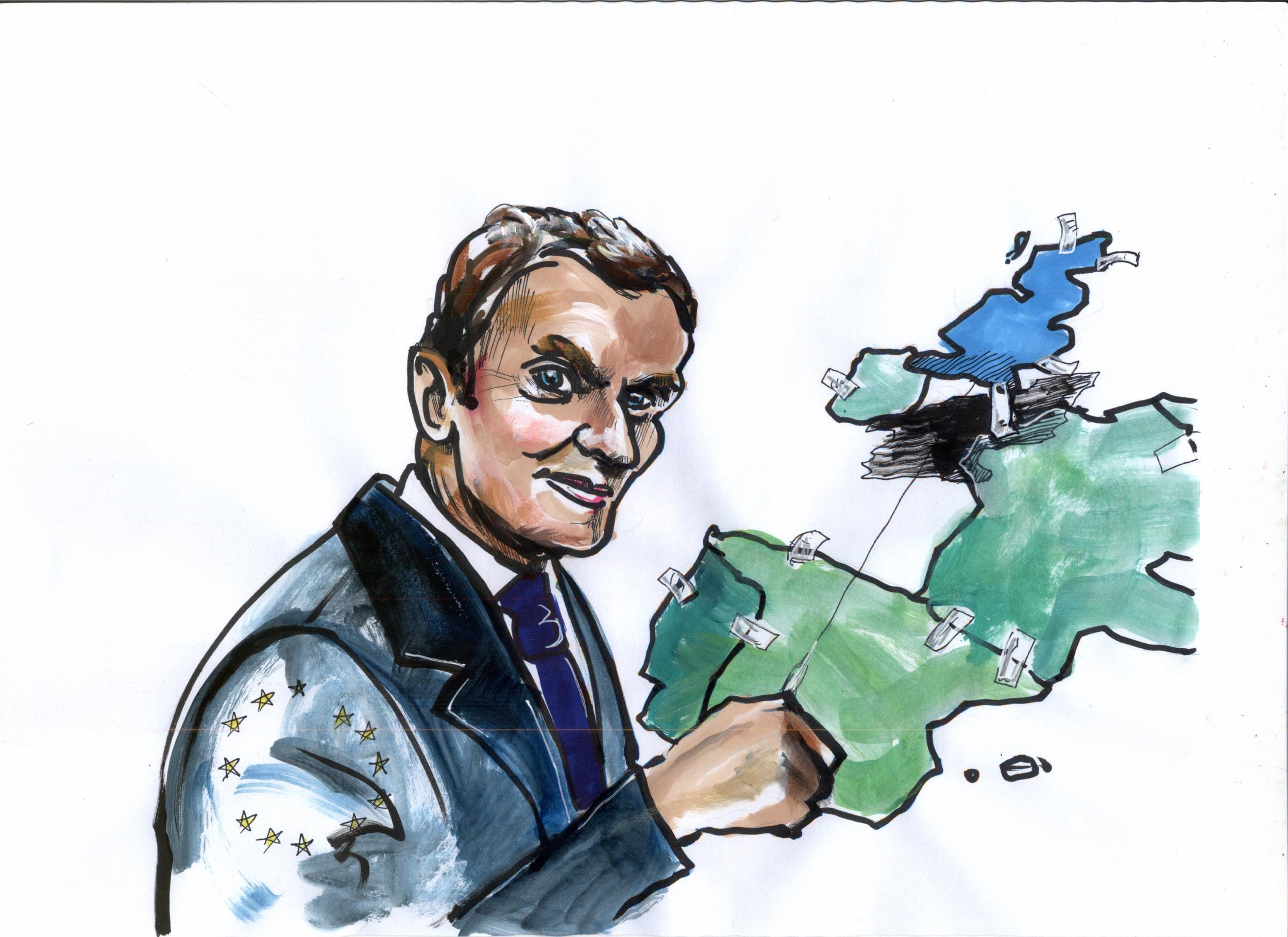

It comes as little surprise that the EU reacted quite strongly in face of what has been called a “Rechtsrutsch” (slide to the right) primarily concerning the referendum and the elections. After the immigration initiative passed, the EU initially rejected any negotiation on the bilateral agreements and deprived Switzerland of Horizon 2020 and Erasmus+ funding, which had subsidized research. Euro-Swiss relations were further damaged by Switzerland’s exit from the Euro cap, which increased the value of the Swiss franc by 30 percent and damaged both economies.

These events have sparked a reaction from the Swiss population that can best be seen in the RASA (Raus aus der Sackgasse/Out of This Dead End) initiative. The initiative, which is not affiliated with any party, seeks to block the referendum from February 9th from being enacted. On September 27 the initiative reached the required number of signatures, and was submitted over a year before the expected deadline. The short time it needed to be submitted and the variety of public figures supporting it show that there was an overall positive response to the initiative. In the coming months, there should be a set parameter regarding the quotas demanded by the immigration referendum, which were left vague at the time of the voting in 2014. Afterwards, it will be sent to the parliament, which will ratify its legislative implementation and call on the Swiss population to vote on it. This second round of voting on the immigration referendum is expected to take place at the end of 2016, almost at the same time as the first round of voting for its counter-referendum, the RASA initiative.

These events have sparked a reaction from the Swiss population that can best be seen in the RASA (Raus aus der Sackgasse/Out of This Dead End) initiative. The initiative, which is not affiliated with any party, seeks to block the referendum from February 9th from being enacted. On September 27 the initiative reached the required number of signatures, and was submitted over a year before the expected deadline. The short time it needed to be submitted and the variety of public figures supporting it show that there was an overall positive response to the initiative. In the coming months, there should be a set parameter regarding the quotas demanded by the immigration referendum, which were left vague at the time of the voting in 2014. Afterwards, it will be sent to the parliament, which will ratify its legislative implementation and call on the Swiss population to vote on it. This second round of voting on the immigration referendum is expected to take place at the end of 2016, almost at the same time as the first round of voting for its counter-referendum, the RASA initiative.

It is quite paradoxical to vote at the same time on a referendum that supports immigration and on a referendum that opposes it. Both initiatives were strongly supported at the time of their proposal, yet it is still to be determined whether the Swiss population, taking into consideration what happened after the first initiative passed, will favor a global and open solution or follow the already present xenophobic and conservative trend. Moreover, this decision means that the Swiss population has completely shifted its stance in just one year, and is simply switching from one idea to the other. Can this dichotomous choice be justified, or is it an abuse of direct democracy? The overuse of direct democracy has made it lose its value, which can be seen in the low Swiss voter turnout for referenda and popular initiatives (even the immigration referendum, the main referendum in recent years, only had a 57 percent voter turnout).

- T. Husbands, a professor at the London School of Economics, calls Switzerland “a democracy in crisis” because of its attitude toward direct democracy, and voting turnouts reflect his view. If one compares the turnout for the immigration initiative to the turnout for referenda a year later (March 2015), one can see that participation has decreased by almost 25 percent. Parliamentary elections are going even worse, with turnout steadily dropping over the last 70 years.

How can Switzerland revitalize direct democracy, a value so central to its identity? It is quite difficult to even imagine the country without such a process, but there is a need to instill efficiency and prevent “on-and-off” referenda. A major reason for the low voter turnout is that the population feels disconnected from the process of direct democracy itself, especially since most initiatives only voice the concerns of one party and are used to promote political agendas that are then refused by the government. Furthermore, demagogic parties use the low voter turnout in their favor, using their support platform to gather votes while other parties mostly ignore the referendum, which is then met with little opposition. Interestingly, the electorate has changed to abide by this situation, resulting in a generally conservative voter base in referenda. This can be seen in the general results of referenda, which tend to disregard the position of minorities. This “tyranny of the majority” needs to change, yet the fact that it is directly represented by both conservative parties and the voting electorate presents a significant challenge to overcome.

In order to resolve this issue, referenda could require a greater number of signatures, which would increase popular participation, undercut unclear initiatives and reduce their use for demagogic purposes. Furthermore, referenda could abandon the yes/no format to accelerate their implementation and efficiency and instead use a more specific voting format that would give a sense of the extent to which the Swiss population wants to enact a referendum. In addition, the promotion of actual direct democracy (deriving from the citizens rather than parties), in which the state helps activists with legal analysis of proposals and a media presence, could truly revitalize civic engagement and widen the standpoints of the electorate.

There are many valuable potential solutions to the Swiss direct democracy dilemma, yet the current structure would in all likelihood not permit such a change. One will have to see how the immigration and SEVI referenda turn out to draw an effective strategy for the future.