ISIS or ISIL or Just IS?

As the Islamic State (IS) stampedes over the Iraq-Syria border, the national boundaries that partition the Middle East have seldom seemed less legitimate. The division of the Middle East into independent states, a product of colonial machinations, yielded borders that have been relatively unchanged for almost a century. Because IS ignores these borders and possesses no international legitimacy, it has been dismissed as a non-state actor. If we call IS a terrorist upstart, a paramilitary group, or an insurgency, then it threatens only the Iraqi and Syrian people and not our international world order. But if those internationally sanctioned borders are truly collapsing, then it is worth exploring if IS is really so dissimilar from a modern nation-state.

The borders that define the modern Middle East did not exist at the dawn of the twentieth century: the entire region was still nominally controlled by the Ottoman Empire. But despite the Ottomans’ valiant attempts at reform, European interventions had left the empire decentralized, indebted, and on the verge of collapse. When World War I finally rendered traditional balance-of-power concerns irrelevant, Britain and France set to work on their vision for a post-Ottoman Middle East.

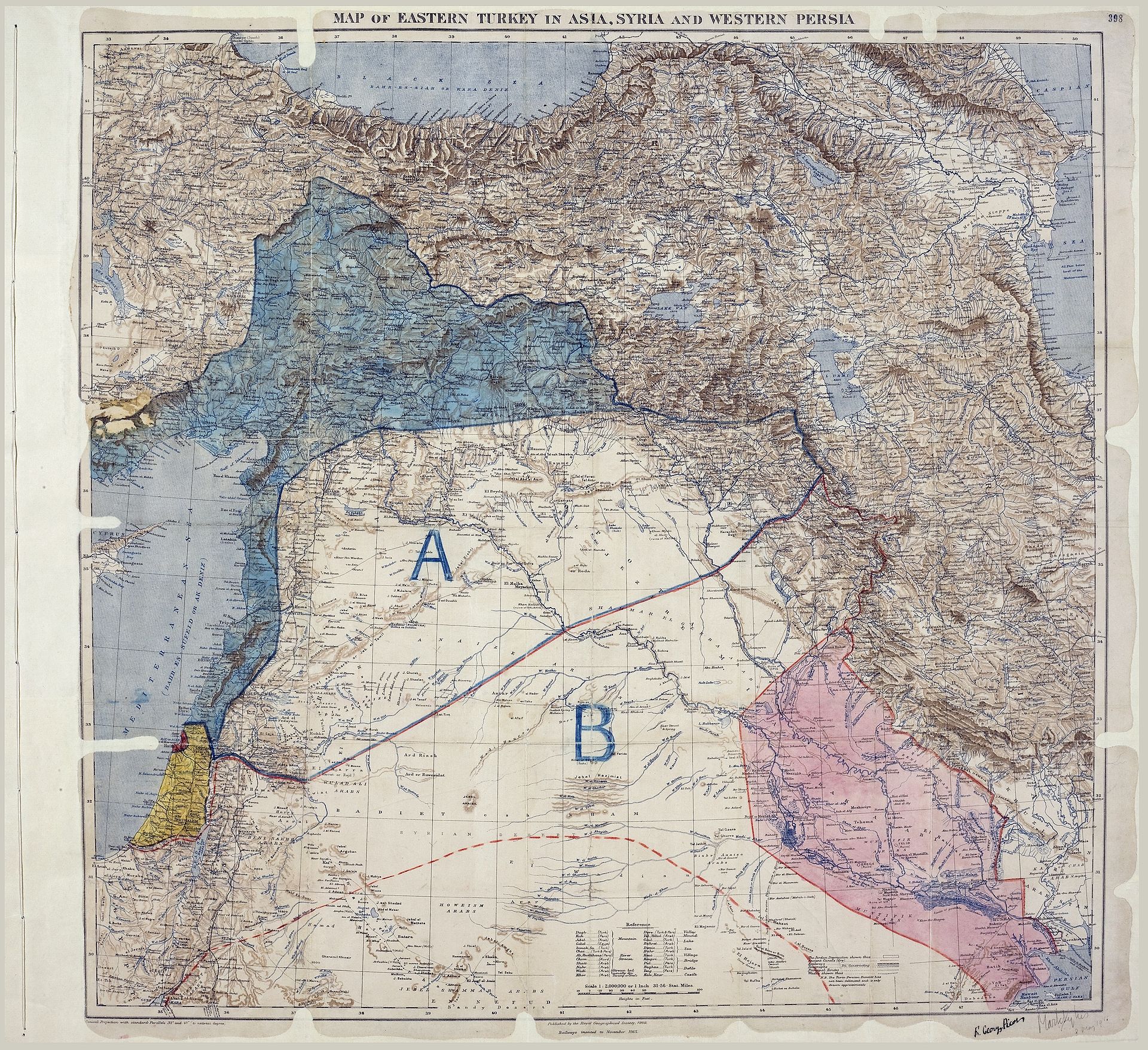

There were many proposals for such a vision. Local national movements were existent but nascent, and so some believed that Arabs across the region should be united in a single Arab state. The British comissioner in Egypt, Henry McMahon, explicitly promised such a state to the Sharif of Mecca. At the same time, local nationalists envisioned self-determination on a more regional level, arguing that the interests of Arabs in, say, Jaffa and Jerusalem, were fundamentally different from those in Damascus and Aleppo. The Kurds, meanwhile, saw ethnicity as the root of nationalism and sketched out the borders of a state with a Kurdish demographic majority. But the map of the Middle East that ultimately won out was essentially drawn in single international treaty: the Sykes-Picot Agreement of 1916. In this secret treaty, Britain and France staked out their spheres of influence across the region.

As this map shows, the boundaries outlined in Sykes-Picot are indeed remarkably similar to today’s internationally recognized borders; a direct comparison can be seen here. The issues articulated in the text of the agreement—railroad construction, water allocation, tariff control, among other things—hint at the ways in which this map became a reality. The administrative rights that the British and French gave themselves, which in some areas included “such direct or indirect administration or control as they desire,” created political and economic institutions that enjoyed the backing of wealthy Europeans and the approval of the League of Nations. As these institutions shaped and were shaped by local nationalist movements, they became the foundation of future Middle Eastern states.

The collapse of Iraq and Syria has brought the power of this process into question. If we relinquish our understanding of statehood in today’s international world order, the Islamic State has in many ways already succeeded. The newly-declared caliphate cannot vote at the United Nations, and it cannot receive funds from the World Bank. It does not have diplomatic recognition from its neighbors, and it does not issue passports. It does not even appear on Sporcle’s world map quiz. But it does have one very important charactaristic of a state: a monopoly on violence within its territory. Though IS certainly claims more land than it actually controls, there truly is an area in which it is the sole organized force. If warmaking makes the state, then IS is well on its way to success.

Perhaps it is difficult to think of the Islamic State as an actual state because the vocabulary we use to discuss the region is so entrenched in our political maps. The media’s confusion over the organization’s name—ISIL or ISIS?—demonstrates the difficulty of escaping to a time before Sykes-Picot.

The debate over that final ‘S’ or ‘L’ comes from the organization’s Arabic name, al-Daula al-Islamiya fil-‘Iraq wal-Sham. The Shami region, which encompasses swathes of modern-day Israel, Palestine, Jordan, Lebanon, and Syria, is absent from any modern political map. While the term “Syria,” or perhaps Greater Syria, would have once referenced the same region, only historians now understand it as such. The term “Levant” tends to suggest a more accurate image of the area in question, but it is ahistorical and it carries an Orientalist flavor that undermines the group’s goals. But though neither Syria nor the Levant adequately conveys the idea of al-Sham, there is no better alternative; we are unlikely to see journalists referencing geographical landmarks, latitude and longitude, or long-gone kingdoms in an attempt to appropriately name a militant organization. The elusiveness of al-Sham points to onlookers’ failure to envision an alternative to traditional borders even as IS rapidly pursues such an alternative.

It is important to note that the idea of a modern Islamic state is not quite as radical as the pictures of black-masked, flag-waving gunmen would suggest. After all, the Middle East is already home to an extremely powerful state that uses religion as the foundation of its nationality: Israel. Israel’s self-identification as a Jewish state has created a country in which a fifth of the inhabitants are counted as citizens of the state but not as members of the nation. The world has managed to condone the legitimacy of this state even though its religious identity has lead to blatant racism. Israel has achieved a large measure of military prowess, economic prosperity, and political stability (in other words, success as a modern state) without truly resolving the crises that come from twisting religion into nationality. If a Jewish state exists, there is nothing about the idea of an Islamic state that is fundamentally incompatible with modern nationalism.

Of course, it is far too soon to predict what the Islamic State will become. World powers and regional powers alike have condemned IS, and their condemnation could easily transform into tangible action that ends IS’s run. As of right now, the failures of the existing Iraqi and Syrian regimes left a land full of people but lacking in state control. Historically, such situations have proved to be fertile ground for the emergence of new regimes, and the same may happen today despite the international community’s trepidation. The success of IS’s bloody rise should force us to question if the trappings of international legitimacy are truly necessary for the creation of a state.