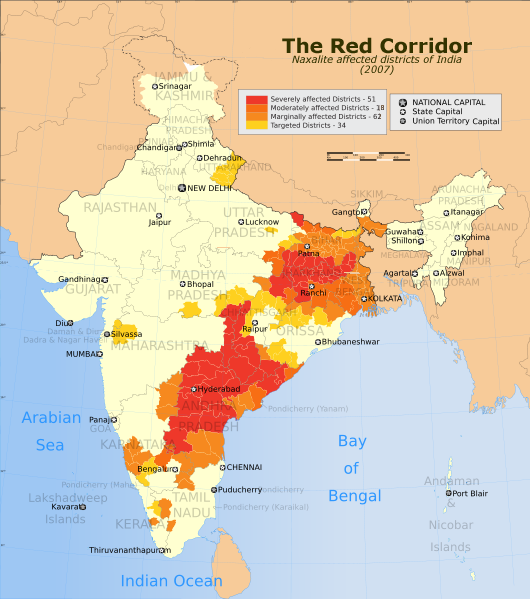

The Red Corridor

India’s rise as an emerging economic superpower has been nothing short of spectacular, and has certainly captured the world’s attention over the last decade. However, in the vast tracts of forests in the northeastern portion of the country—far away from the public’s gaze—India’s people do not experience the fruits of economic progress. Instead, they have constantly been subjected to violence and exploitation by the Indian state and have thus remained in destitute poverty. These forgotten people serve as a constant reminder of the multi-dimensional inequalities of caste, class, gender, and region that still afflict millions of Indians today.

The people who live in the forested, hilly tracts of Eastern and Central India are known as adivasis, which literally means ‘first inhabitants,’ and are essentially a collection of indigenous tribes that follow a lifestyle tied up with the forest. They have suffered throughout India’s independent history at the hand of the state’s oppressive forest policies and have not had any access to vital public services. As eminent Indian historian Ram Guha notes, “the traditionally held-rights of the forest communities have been progressively curtailed through the development of forest policy, management and legislation.”

For most adivasis, an interaction with state officials leads to extortion and violence. Forest officials, police constables, and local bureaucrats collude and engage in extortion rackets. For example, tribals that are caught cultivating their plots in the forest will be quickly taken to the police station and charged for encroaching on ‘reserved’ forestland. Officials then usually demand a bribe, after which the charges are dropped. If the adivasis are found carrying firewood, the local police constables are known to physically assault them.

The livelihoods of the adivasis are intrinsically tied to the forest—a fact that the Indian state has routinely ignored. The adivasis lifestyle clashes with the formal laws of the land, creating opportunities for extortion, abuse and violence that has been a regular feature in the daily life of the tribals.

Traditionally, the Maoists, or Naxalites as they are commonly referred to, represented the interests of the lower-class peasant. However, since the expansion of the Indian economy in 1991, the Maoists have shifted their focus to battles over the displacement of the adivasis for mining and infrastructure projects, the creation of Special Economic Zones for international mining companies, and wildlife conservation. The tribal people have suffered immensely in the era of economic liberalization as private international companies rush in to secure valuable natural resources (such as bauxite and iron ore), displacing the adivasis in the process. Those who are displaced rarely receive compensation and rehabilitation—further indication of the callousness with which the Indian state has treated the adivasis.

However, the Maoists often find themselves in collusion with the very institutions that they claim to be fighting against. Maoist activity is most noticeable in areas rich in natural resources. Mine owners claim the only way to stop Maoist attacks is to hand over a share of their revenues to the rebel groups. Ethnographic accounts reveal that the Maoists regularly engage in extortion rackets where they demand a steady stream of money from mining companies in exchange for protection.

Thus, there is an inherent conflict in the Maoist ideology between the goals of representing the interests of the adivasis and funding the armed struggle to overthrow the state. The money needed to equip Maoist foot soldiers means that the rebels end up negotiating and working with the very mining companies that are responsible for the plight of the adivasis. Moreover, the adivasis are often forced to ‘volunteer’ community members to fight in the armed revolution. The coercive tactics Maoists use for recruitment means the adivsasis are often terrorized by the very people that were supposed to be protecting them. Some adivasis have even been killed on suspicion of being police informants and collaborators.

The adivasis now find themselves trapped in the conflict between the state and the Maoists. They are routinely displaced from their lands, exploited and physically abused by both parties(even though the Maoists claim to be fighting on their behalf). The adivasis are symbolic of the limited reach of Indian democracy and economic progress. Their plight highlights the need to pay much greater attention to the demands and interests of those that are most deprived in Indian society, and to integrate their voices into the national conversation.

Otherwise, India risks remaining, as economist Amartya Sen writes, “Islands of California in a sea of sub-Saharan Africa.”