So how unique was Sandy?

There is a common perception in the public sphere that short-term weather events are signals and symptoms of long-term climate change. Every time there is a major weather event, such as the landfall of Cyclone Phailin on the East Indian coast earlier this month, hordes of activists, many of them bloggers, are quick to point the finger at the most likely culprit: global warming, specifically human-induced climate change. While there may be a link between warming and long-term meteorological variability, any connection between climate and current weather events is tenuous at best. NOAA, in fact, released a study in 2008 stating “it is premature to conclude that human activities – and particularly greenhouse gas emissions that cause global warming – have already had a detectable impact on Atlantic hurricane activity.” The study further indicated that there will be “a likely decrease in the global numbers of all tropical storms,” despite chances of increased storm intensity.

There is a common perception in the public sphere that short-term weather events are signals and symptoms of long-term climate change. Every time there is a major weather event, such as the landfall of Cyclone Phailin on the East Indian coast earlier this month, hordes of activists, many of them bloggers, are quick to point the finger at the most likely culprit: global warming, specifically human-induced climate change. While there may be a link between warming and long-term meteorological variability, any connection between climate and current weather events is tenuous at best. NOAA, in fact, released a study in 2008 stating “it is premature to conclude that human activities – and particularly greenhouse gas emissions that cause global warming – have already had a detectable impact on Atlantic hurricane activity.” The study further indicated that there will be “a likely decrease in the global numbers of all tropical storms,” despite chances of increased storm intensity.

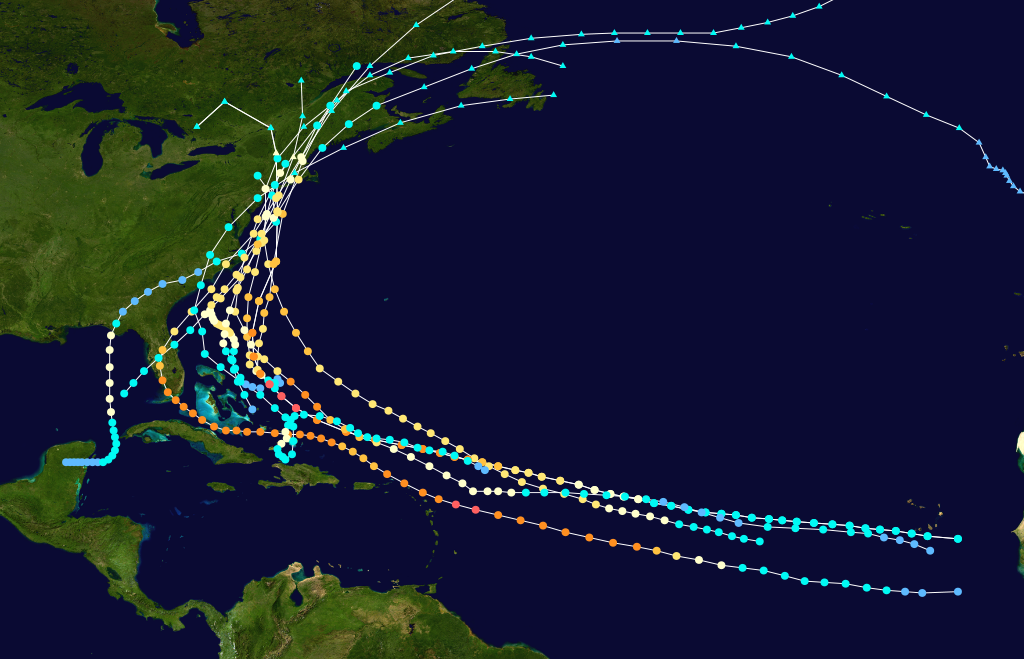

The most famous incident which highlights the disconnect between the fact of climate change and the farce of environmental activist propaganda is the landfall of Hurricane Sandy on the New Jersey coastline last year. Media outlets spoke of a 100-year event striking New York City – some touted Sandy as a 500-year storm, while other more misguided individuals declared that nothing like Sandy had ever been experienced. Superstorm Sandy is what it became known as, perhaps a relevant title considering the extent of the damage incurred in the wake of the storm. Yet how unprecedented was Sandy?

Over the summer, I interned as a research assistant at an engineering and design firm called Sherwood Design Engineers. One of my tasks was looking over New York’s meteorological history (patchy records date back to the 1600s, with a more consistent daily record emerging by the 1870s) for patterns and long-term changes. The hurricane record proved most interesting. The Great Colonial Hurricane, for example, struck southern New England in 1635 with a twenty foot storm surge in Narragansett Bay. A thirteen-foot storm surge in August 1817 completely flooded Manhattan Island up to Canal Street. Yet another hurricane in 1893 was nearly wholly responsible for the disappearance of Hog Island, a resort island that existed near the Rockaway Peninsula, which finally succumbed to the ocean in the early 1900s.

Multiple hurricane strikes continued into the 20th century. The Long Island Express of 1938 proved the second most intense hurricane at landfall in New England history, after the Great Colonial Hurricane mentioned earlier. Evidently, the Northeast, including New York City, is no stranger to tropical systems. “Snowicanes,” another term used to describe Sandy’s unique character, were also recorded in 1782, 1804, and 1841. Hurricane Sandy was a devastating storm, no doubt, but we can’t say with certainty that it was unprecedented, or that it was the result of human activity. Looking through meteorological records, many storms have impacted the region, so why was Sandy so surprising?

One explanation may be the absence of significant hurricanes directly striking the Northeast. Towards the second half of the century, there was a lull in hurricane activity in the area. Of course, tropical systems continued to impact the region – Gloria in 1985 and Floyd in 1999 are two examples – but no significant damage was incurred.

By highlighting the frequency of significant tropical cyclones striking the New York City region, this article is not meant to reduce the importance of finding solutions as quickly as possible; rather, it is meant to heighten awareness of the special risk that New York City has always faced, but has never fully addressed. While Hurricane Sandy has provided the temporary impetus to implement innovative flood reduction strategies, we must remember that there might not be a significant hurricane for decades, but it will come eventually, as these meteorological records prove. The marked absence of catastrophic hurricanes between 1938 and 2012 lulled the city into a false sense of security, allowing development close to shore without necessary protection.