Over Defense

Four months prior to the September 11 attacks, Harvard University Professor Richard Falkenrath published an article in the Journal of Studies in Conflict & Terrorism that argued for a drastic reduction of government spending on counterterrorism. He suggested that there was little evidence of any real threat to Americans’ safety and that spending on counterterrorism was a waste of resources that could be better spent on other domestic programs. Following the horrific attacks in 2001, however, Americans developed a rally-round-the-flag mentality and President George W. Bush’s approval rating briefly rose to 90 percent in the weeks subsequent to the attack. The United States completely revamped its operations, putting a core focus toward increasing its counterterrorism capabilities. The FBI doubled its number of counterterrorist agents and set its number one priority to “protecting the United States from terrorist attack.” The total dollar amount spent on domestic counterterrorism has continued to climb ever since, and for fiscal year 2013, the Congressional Budget Office expects the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) budget to be $68.9 billion, or roughly $526 per household.

Thousands of politicians and corporations have profited from this recent expansion of counterterrorism efforts. In the last decade, the government spent over $570 billion on the DHS alone – not to mention the additional allocations to agencies like the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) and National Security Agency (NSA), whose budgets are classified. The $570 billion allocation alone is more money than the nation spent on groceries last year, according to the USDA Economic Research Service. This is a big industry, and its growth has been astonishing. With the horrifying attacks of 9/11 still prominent in the public consciousness, the United States spent $22 billion on the DHS in 2002. However, after more than a decade with no major terrorist attacks, the funding has ballooned to over three times that amount. US citizens have sacrificed many resources to fight the war on terror, including their tax dollars and civil liberties.

Some experts, like The Ohio State University professor John Mueller, try to assure us that there is no real threat to America. He argues that the greatest harm inflicted by terrorism is the ill-considered overreaction and fear it creates in the wake of an attack. Others, like retired U.S. Army Colonel David Hunt, counter that the next big attack is right around the corner and that we have done far too little to combat it. Both of these experts rely on their analysis of current global events and overall trends in terrorist activities. The problem, however, is that terrorist threats are organic in nature and extremely unpredictable. If the threat were calculable in the same way as a dice roll, we could simply determine an appropriate risk management level and adjust our counterterrorism efforts accordingly. However, in the randomness and chaos of today’s world, it is not that simple. There needs to be a different approach to striking the proper balance between economic burdens and national security.

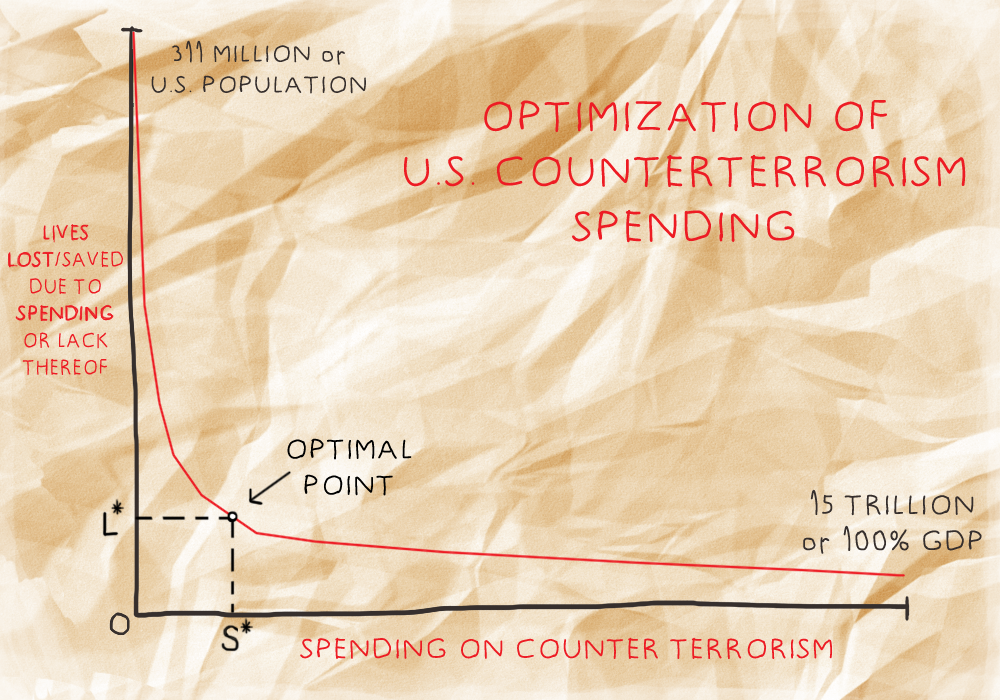

If terrorist attacks were the only threat facing our nation, one could easily argue that we choose a point of spending where we come close to minimizing all US casualties. Unfortunately, this is not the world in which we live. We must take into account the burden that the spending on counterterrorism imposes on society. If it becomes too large, it could be more devastating than the terrorist attacks it prevents. We choose not to spend an exorbitant amount on police and firefighters; rather, we rationalize our approach and have come to accept a certain amount of crime and death. In the same way, however, we also become angered and reactive when the level rises above what we deem a reasonable threshold. Moreover, we, as a society, try to determine the level at which we optimize our economic investments through taxes and the outcomes of crime fighting. When crime skyrockets, we rally in the streets and demand more protection even if it requires an increase in government revenue. In contrast, when crime is low, we complain about the tax level and are as a whole willing to cut public safety investments in return for lower taxes and a reallocation of the resources.

Although many experts attempt to manipulate our fears of another attack or our anger about government over-spending, the answer is not as complex as they make it appear. We simply need to find the point at which our spending has the greatest amount of efficacy, and, if the number of potential fatalities is reasonably low, set our spending accordingly.

According to the FBI, there have been 318 terrorist attacks in the United States from 1980-2005, resulting in a total of 3,178 deaths. If, however, we take out the 2,996 deaths from the 9/11 attacks, which were counted as a single event, we have an average of less than one death per attack. Furthermore, the average number of attacks per year from 1980 through 2000 was 13.4, while from 2001 through 2005 it was only 7.6. Although the frequency of attacks during the 1980s and 1990s was almost double that of 21st century, why were we so content at the time with an almost nonexistent counterterrorism policy? There were more attacks each year, although none of them mounted to the level of tragedy as that of 9/11, the potential was there. Just because the terrorists executed fewer attacks does not mean that they were not trying. Was the horror of 9/11 just a freak occurrence?

Predicting organic events such as the terrorist attacks of 9/11 is not a scientific endeavor. Although studying terrorist events may lend some insight, Oxford University Professor Nassim Taleb refers to their suppositions as “epistemic arrogance,” or, arrogance despite our own limited knowledge. Furthermore, he questions, “Why on earth do we predict so much? Worse, even, and more interestingly: Why don’t we talk about our record in predicting? Why don’t we see how we (almost) always miss the big events?” So why, then, if our abilities are so limited, do we put such vast resources into trying to prevent an attack we can never predict?

Columbia professors Brigitte Nacos, Yaeli Bloch-Elkon, and Robert Y. Shapiro conducted a study that illuminates some of the underlying sentiment responsible for this mentality. Through an analysis of public polls from September 2001 through December 2005, the professors found that public confidence in the government’s ability to protect citizens from terror attacks spiked immediately after the attacks, but waned thereafter. By the summer of 2005, they found that “a majority of the public (56%) was not too confident or not at all confident in their government’s ability to prevent terrorism in their own communities.” Additionally, they found that “a majority of Americans (54%) felt that more could be done in terms of prevention, while only 43% believed that the United States was doing all it reasonably could.” These two results help us understand why we are willing to sacrifice so much. They show that not only do we feel that more could be done to prevent terrorism, but also that we feel that what we have done so far does not make us feel safe. However, we already spend $526 per household per year on domestic counterterrorism. So is it irrational to spend even more on protecting the lives US citizens from such an unpredictable and unlikely event?

If we are truly concerned with protecting the lives of US citizens, then we must reallocate our resources to areas that have a greater impact on a larger number of people. For example, 2,996 lives were lost on the day of the 9/11 attacks. In comparison, in that same year 559,354 died from cancer, 42,196 lives died in car accidents, and 700,142 died from heart disease. It boils down to a betting game: the likelihood of dying from any one of these more likely scenarios is far higher than from a terrorist attack. Although we should never forget 9/11, it is time, as hard is it may be, to move on and to use our money to more effectively to protect America. Since a major consideration of our elected leaders is re-election, we must be the voice of reason that propels them to change our current policies.