Briefing: Immigration

In the 2012 election, an overwhelming majority of first-generation Americans voted in favor of Democratic candidates over Republican ones, bringing the issue of immigration reform to the forefront of governance. With 71 percent of Latinos having voted for President Barack Obama, many Republican politicians, including Marco Rubio and Jeb Bush, both from Florida, have voiced concerns that their party needs to change its stance on immigration policy to account for a rapidly changing American demographic.

In the 2012 election, an overwhelming majority of first-generation Americans voted in favor of Democratic candidates over Republican ones, bringing the issue of immigration reform to the forefront of governance. With 71 percent of Latinos having voted for President Barack Obama, many Republican politicians, including Marco Rubio and Jeb Bush, both from Florida, have voiced concerns that their party needs to change its stance on immigration policy to account for a rapidly changing American demographic.

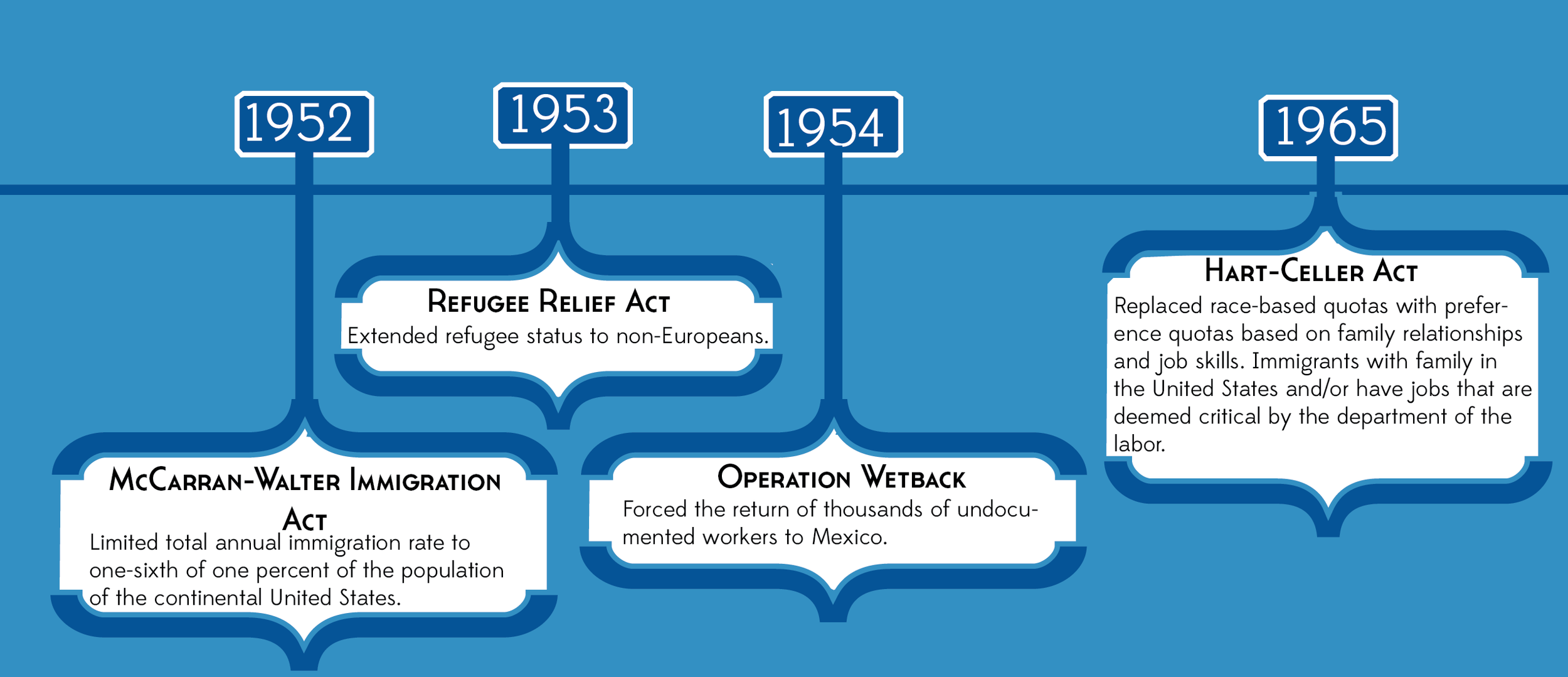

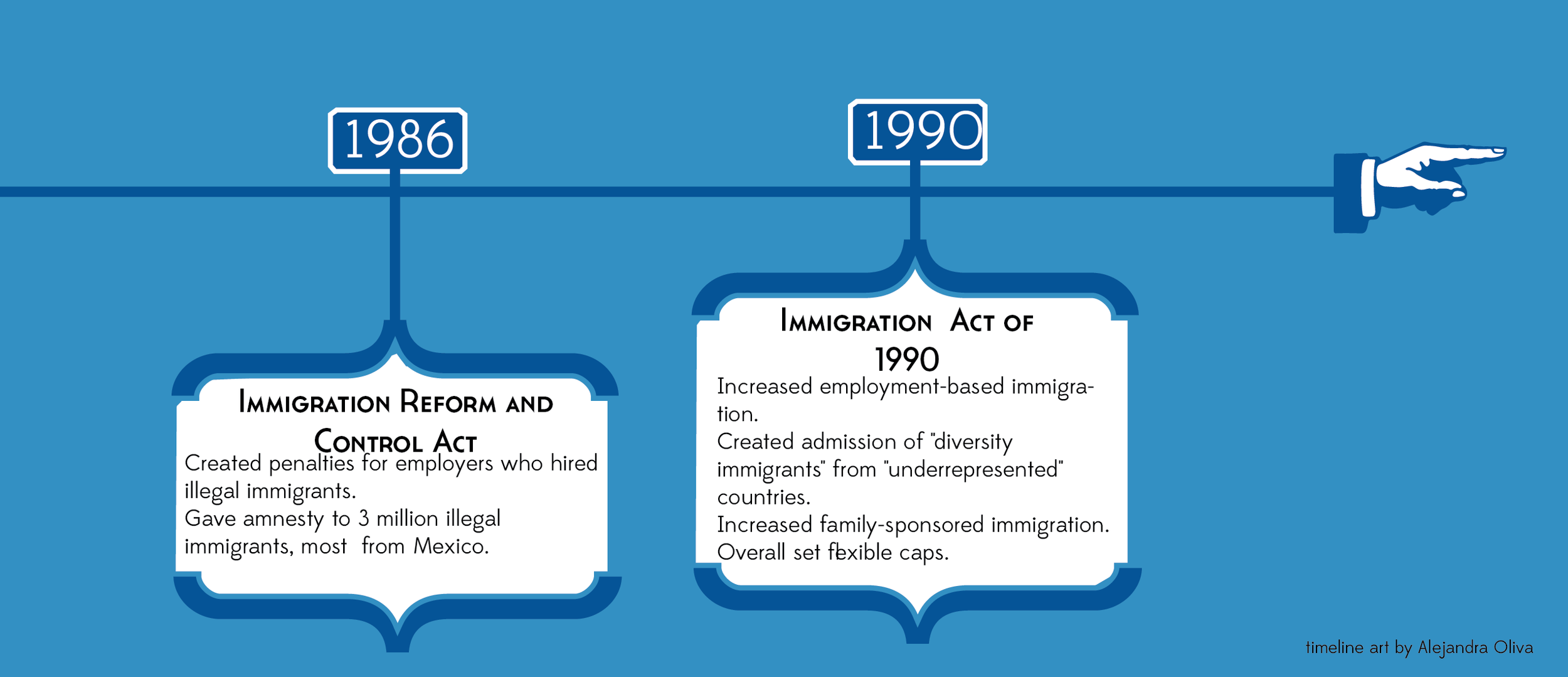

In 1986, the Immigration Reform and Control Act legalized the status of many undocumented residents in the United States, but the hiring of workers without proper work authorizations remained illegal. While a subsequent Immigration Act that passed four years later increased and established a more flexible cap on the number of legal immigrants allowed into the United States, the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act of 1996 lead to massive federally-imposed deportations by requiring those who had unlawfully immigrated to the United States to leave the country until they could acquire a pardon.

In 2001, Senators Dick Durbin (D-IL) and Orrin Hatch (R-UT) introduced the Development, Relief, and Education for Alien Minors (DREAM) Act, which provides for conditional permanent residency and federally subsidized financial aid to allow the children of undocumented residents to pursue post-secondary education. Despite subsequent attempts to pass the DREAM Act in Congress, most recently by Harry Reid (D-NV), the bill has never become law. President Barack Obama’s executive order in 2012, nonetheless, directed his U.S. Department of Justice to stop the deportation of immigrants who fall under the provisions originally proposed in the DREAM Act.

Apart from the DREAM Act, other Congressional attempts toward immigration reform have included the bipartisan proposals of Senators Charles E. Schumer and Lindsay Graham. In 2010, they introduced a legislative blueprint requiring the use of biometric identification to ensure that only documented citizens are hired for jobs. They also brought forward a proposal to improve border security to prevent the unlawful crossing of the American-Mexican border while simultaneously constructing a means to admit temporary workers into the United States and give those already in the country an opportunity to become citizens. Despite the fact that their resolutions failed to reach the Senate floor, and that the midterm elections placed immigration reform on the backburner, Schumer and Graham announced after the 2012 elections that they are planning to revive their proposals.

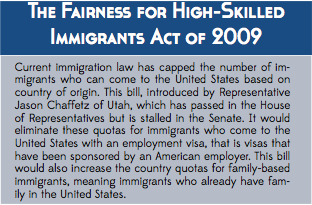

In December 2012, it became evident that the Obama administration had already begun gearing up to launch a communications strategy to promote immigration reform after its negotiations on the fiscal cliff draw to a close. As officials in the Obama administration told the Los Angeles Times, President Obama intends to start working with Congress on a comprehensive bill that would not only create a path to citizenship for the large number of undocumented workers already residing in the United States, but would also create disincentives for future unlawful immigration by improving border security, punishing employers for hiring illegal immigrants, and encouraging the immigration of high-skilled workers through legal means. It is uncertain at this moment whether the Obama administration will work closely with Senators Schumer and Graham to advance their proposed measures that includes a tough but fair approach toward amnesty, or will instead focus predominately on provisions that are more popular with conservatives, such as visas to assist entrepreneurs and high-tech workers.

In the aftermath of the Supreme Court’s decision to uphold some but not all of the provisions in Arizona’s SB 1070, it is inevitable that the path toward immigration reform will involve a delicate dance between local and federal government. What can be changed, however, is whether members of both political parties work to creating substantive immigration reform.

Scott L. Minkoff, Ph.D.

Assistant Professor of Political Science, Barnard College

Taylor Nagel

Barnard College, 2013

Leah Rosenberg

Barnard College, 2013

The election-induced reemergence of a national discussion about immigration policy has centered on the electoral prospects of Republican candidates and – to a lesser extent – the prospect of residential privileges for millions of immigrants illegally in the country. Whether this discussion will result in federal legislation remains to be seen. In the interim, it is worthwhile to take stock of the broader policy context of American immigration politics. Indeed, the federal government, states, and local governments (often in combination with one another) have been experimenting with immigration policies for the last several decades. Driven by contrasting beliefs about the meaning of American citizenship and the rights of non-citizens, these experiments have challenged the limits of the federal bureaucracy and our expectations about community. Simultaneously, these sub-national efforts force us to confront serious theoretical and practical questions about American federalism. Primarily: Who has the authority to regulate immigration? And, what purpose do sub-national immigration efforts serve?

While the Supreme Court has made it clear that the national government is the enforcer of US citizenship, public policies in our federal system suggest murkier waters. The immigration scholar Monica Varsanyi has pointed out that the “contemporary devolution of select immigration powers is creating both opportunities and requirements that local governments discriminate against people as immigrants.” One example of this is the federal 278(g) program that allows state and local police to partner with federal authorities in order to collectively enforce immigration laws (including raids on businesses employing illegal immigrants). But the fact remains that without the help of the federal government, there is little that sub-national governments can do to actually remove people from the state or country.

State and local governments do maintain some flexibility to independently engage with policies that impact non-citizens. The fallout from Arizona’s “Support Our Law Enforcement and Safe Neighborhoods Act” is a good example. In U.S. v. Arizona (2012), the Court pre-empted the most of the enforcement-oriented aspects of Arizona’s tough immigration law but left intact the law’s requirement that police check the immigration status of anybody who has been arrested if there is suspicion that the person is in the country illegally. (Both Alabama and Georgia have passed similar policies.) What remains of these state level efforts is not only consistent with historical Constitutional standards but also reflective of the contemporary politics of immigration federalism. Indeed, the immigration policies being formulated and enacted by state and local governments are not trivial but they are also – by rule and intention – fundamentally different than uniformly federal efforts. Whereas federal immigration policy is about defining and enforcing legal status, sub-national policy efforts are about defining the economic and social bounds of community.

These social and economic bounds can be contracted with exclusionary policies or expanded with inclusionary policies. Large-scale exclusionary policy efforts (like Arizona’s) have received the majority of attention but narrower exclusionary examples abound. Electronic verification (E-Verify) is a tool administered by the Social Security Administration and the Department of Homeland Security that allows sub-national governments and private businesses to check the immigration status of their employees (within a non-trivial margin of error). It was even touted as an important tool for fighting illegal immigration by Mitt Romney during the campaign. Throughout his 2010 Florida gubernatorial campaign, Rick Scott strongly supported an E-Verify mandate for public and private employers but upon taking office he found that the politics of immigration reform were more complicated than he anticipated. The Florida citrus industry pushed back and Scott modified his position to support E-Verify only for public contractors and subcontractors. Whether or not E-Verify is an effective tool for reducing the desirability of places as destinations for illegal immigrants remains an open question. What is clear is that E-Verify is a way for communities to say: “You are not welcome here… even if we cannot force you to leave.” This appears to have been the case in Rhode Island where an E-Verify rule put into place by Governor Donald Carcieri in 2008 was repealed by Governor Lincoln Chafee in 2011. Chafee argued that E-Verify had “caused needless anxiety within our Latino community without demonstrating any progress on illegal immigration.”

Local governments have implemented exclusionary policies, too. Illegal Immigration Relief Acts (IIRAs) are local ordinances that seek to regulate employment and housing. These measures have been considered in cities in over 30 states. A 2006 IIRA passed in Hazleton, Pennsylvania made it illegal for landlords to rent to illegal immigrants and for employers to hire them. The Act was pre-empted by a U.S. District Court, but still sent a clear signal to the illegal immigrants in the community. Prince William County, Virginia passed a similarly restrictive ordinance that prevents immigrants access to certain social services and creates a partnership between local law enforcement and U.S. Immigrations and Customs Enforcement (ICE). Other ordinances establish English as the official language. Interestingly, research by Karthick Ramakrishnan and Tom Wong shows that these sorts of policies are driven more by partisan politics than by the size of the Hispanic or recent immigrant populations.

Not all policy efforts are exclusionary. State-level DREAM Acts are an example of inclusive efforts by states to broaden the economic and social community. These laws, which have been enacted by California, Texas, Illinois, New Mexico, and Maryland, allow undocumented students to pay the in-state tuition rates at public colleges and universities and in many cases to access state financial aid and scholarships. Indeed, inclusionary policies are just as much about shaping the bounds of community as exclusionary policies. But just as exclusionary policies are not enforcement policies, inclusionary policies – like state DREAM Act programs – are not paths to citizenship. Nevertheless, it is worth remembering that whatever political space governments have to deal with the illegal immigration problem is not being uniformly used to make the community more hostile to illegal immigrants.

It remains to be seen if federal action will change the dynamics of state and local immigration policy. Our suspicion is that because these policies appear to be driven by expectations of community, anything short of a draconian national law is unlikely to curb local exclusionary policies.

Rodolfo de la Garza,

Professor of Political Science at the School of International and Public Affairs (SIPA) at Columbia University

As part of his presidential campaign, on June 15, 2012, President Obama issued a directive to the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) that it use “prosecutorial discretion” to allow unauthorized immigrants between the ages of 15 and 30 who entered the United States before the age of 16; who continuously resided in the United States since June 15, 2007; and who are currently in school, graduated from high school, obtained a GED/in the process of getting a GED, graduated with an associates or bachelor's degree; or are honorably discharged from the Coast Guard or Armed Forces to remain in the country for two years. Although the directive includes many of the policies contained in the DREAM Act, it does not create a path to permanent legal residency or citizenship. Moreover, unlike the DREAM Act that promises permanent reforms, the directive will remain in effect only through 2016 or until Congress enacts new immigration policy prior to the end of that year.

The directive offers temporary relief to the most innocent and deserving of the undocumented, that is, those who were brought to the United States as children and who have either already made significant contributions to American society or have prepared themselves to make such contributions.

As the National Hispanic Leadership Agenda demands, permanent reforms require two components. First, they must institutionalize the rights of these groups and extend them to all undocumented immigrants who demonstrate that through their labor and behavior they too are contributing to the nation’s wellbeing. Second, the Department of Justice must develop policies designed to curtail anti-immigrant policies at state and local levels. But even such major changes will not provide a viable long-term solution to the immigration dilemma.

The root of the problem is in the continuous reproduction of households that include undocumented immigrant children. This pattern means that the current problem regarding how to deal with large numbers of relatively young undocumented immigrants who have already benefitted the nation, or who are poised to do so in the future, will continuously recur and create demands for new DREAM Acts.

There are three obvious humane responses to this conundrum. The first is to open the border and leave immigration unrestricted; this is politically untenable. The second is to mandate the use of reliable and enforceable employer sanction regime. This is increasingly technically feasible. Employers who hire immigrants and activists who defend all immigrants, strongly oppose such a regime because of doubts regarding its reliability. Such opposition, given the current quality of verification systems, risks making the best the enemy of the good.

Third is to enact legislation countermanding Plyler v. Doe that would greatly reduce the educational rights of undocumented children. Absent Plyler, foreign nationals would be much more likely to demand improved educational opportunities for their children in their countries of origin. This legislation, thus, is not intended and should not deprive children of education. Rather, it would create strong incentives for parents to demand that their home governments provide the services that citizens demand.

Unless the Obama administration commits itself to addressing the roots of our nation’s immigration problem by designing policies that incorporate a verification system and by disincentivizing against future family reunification demands, any reforms it enacts will be unlikely to significantly improve the immigration problem by designing policies that incorporate a verification system and by disincentivizing against future family reunification demands, any reforms it enacts will be unlikely to significantly improve the immigration problems we now confront.