The Fact Check Republic

On March 29, 2012, at 12:52 p.m., Logan Smith, a 25 year-old college graduate, reported on his personal blog that the IRS was to federally indict South Carolina Governor Nikki Haley for tax evasion. Piggybacking on the heightened media attention that surrounded the Republican vice-presidential hopeful, Smith engineered a blog post that would generate controversy, increase web hits, and spread virally. He accomplished all three.

On March 29, 2012, at 12:52 p.m., Logan Smith, a 25 year-old college graduate, reported on his personal blog that the IRS was to federally indict South Carolina Governor Nikki Haley for tax evasion. Piggybacking on the heightened media attention that surrounded the Republican vice-presidential hopeful, Smith engineered a blog post that would generate controversy, increase web hits, and spread virally. He accomplished all three.

At 12:54 p.m., a blogger for The Hill re-tweeted Smith’s story. Exactly two minutes later, the re-tweet caught the eye of Buzzfeed, who also shared the story with its followers. And finally, at 1:14 p.m. on that same day, the story appeared on the Wall Street Journal’s Twitter feed. The next day, the story made the jump from digital to print and headlined the front page of The State of Columbia, South Carolina’s largest newspaper.

Smith’s story, as it turns out, was entirely false. There were no facts, no sources, and no call for quotes. Several hours after publication, after conducting interviews with both Governor Haley and the Department of Justice, the State of Columbia retracted its front-page cover story. Drudge Report, Politico, The Huffington Post, and The Daily Beast also took down their coverage.

This incident was not the first time the news media misreported a story. In June 2012, CNN falsely reported that the United States Supreme Court had declared the Affordable Care Act unconstitutional. In the days leading up to the 2003 invasion of Iraq, Judith Miller, a reporter for The New York Times, wrote front-page articles that confirmed Iraq’s nuclear capability. Her headline story, published on September 8, 2002, erroneously pushed the Bush administration’s war agenda. In the article, she asserted, “Mr. Hussein’s dogged insistence on pursuing his nuclear ambitions, along with what defectors described in interviews as Iraq’s push to improve and expand Baghdad’s chemical and biological arsenals, have brought Iraq and the United States to the brink of war.” Colin Powell, Condoleezza Rice, and Donald Rumsfeld cited Miller’s articles when they made appeals to the United Nations to authorize a preventive strike against Iraq.

Once again, every single one of Judith Miller’s articles was false. Sources were misquoted and, when they proved contrary to Miller’s agenda, ignored. Miller was eventually fired, and Howell Raines, the then-executive editor of The New York Times, resigned.

Critics cite both the Logan Smith and Judith Miller cases as small and large-scale examples of the failures of modern journalism. As New York University professor Clay Shirky contends, gone are the days when journalists were regarded as the most trusted people in America. When Walter Cronkite concluded his nightly newscast with “and that’s the way it is,” people believed him. Today, on the other hand, people are justifiably skeptical of the news media.

Media scholars often regard the period between 1950 and 1975 as the golden age of journalism. Television journalism, a fledgling field, had yet to gain the momentum and following it has today. It was the newspaper, buoyed by the triumphs of reporting on the Pentagon Papers and Watergate, that was lauded by the public as the chronicler of truth. There was a distinct separation between objective news – reporting that briefed readers solely on the facts and provided multiple and opposing explanations for what the facts meant – and subjective news – reporting that provided a single opinion, usually the author’s, on what the facts meant. Objective news was found on the front pages of the newspaper, while subjective news was confined to the editorial section. Subjective news articles were usually constricted to an eighth page and thus became known as “columns.” Unlike objective news articles, which ran every day, columns ran on a bi-weekly schedule because of the longer and more laborious editorial process required.

For newspapers, objectivity was important – not just for upholding standards of fair journalism, but also for staying financially viable. Newspapers used a business model in which their main source of revenue came from advertising, allowing newspapers to be sold at extremely low prices and, sometimes, for free. Unwilling to isolate readers and advertisers, editors elected to solely report the objective facts and stay away from stories that were incited by subjective opinion. This allowed newspapers to appeal to a broad audience consisting of different political and social ideologies, and it was in this mélange of interpretations and beliefs that the truth emerged.

This media culture changed in the late 1980s with the advent of cable television. A new business model emerged in which the dependence on advertising was reduced. Customers paid fees to subscribe to cable news channels like FOX and CNN. Because customers had to pay for channels without specifically picking them, networks did not have to worry as much about isolating customers. With the introduction of a new source of revenue, networks are no longer as dependent on advertisers. This business model, along with already increasingly polarized media, explains why today FOX can be blatantly conservative and MSNBC can be blatantly liberal and neither has to worry about losing cable subscriptions.

What sets cable news apart from other news media is that it is always available. Networks have 24 hours of programming they have to fill, resulting in a demand for content that traditional news cannot satisfy. Thus just as newspaper editors devoted a section of the paper to editorials, television producers devoted timeslots to political talk shows. Starting in the 1980s, news programming hosted by political pundits relayed the events of the day and then provided their own commentary and opinion, provided ratings hits, and became a major source of revenue for the networks. Suddenly television journalism became more popular than print journalism. As media scholars have pointed out, audiences came to view the bias and subjectivity that proliferated on the news networks as the new journalistic norm.

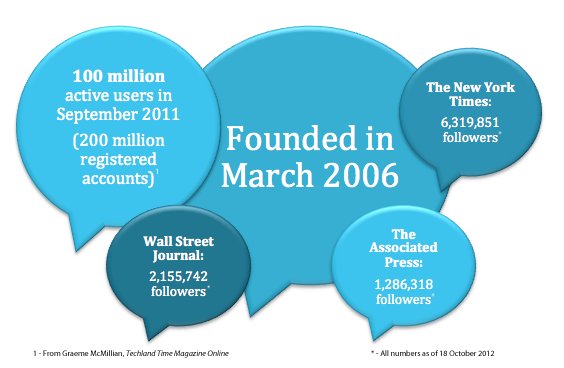

While cable news grew increasingly subjective and profitable, print news remained objective and dependent on the traditional advertising revenue business model. This, too, changed with the development of social media and the growth of the Internet. Although print journalism still struggles with profits, newspapers like The New York Times and Wall Street Journal have raised revenue with online advertising and pay walls. Although the number of actual home and office delivery subscriptions has fallen, newspapers are reaching larger audiences than ever before with social media. Websites such as Twitter, Facebook, and Buzzfeed allow for the rapid sharing of news sites and links to news articles and the advertising opportunities are endless. But beneath the glossy façade of profitability, there lingers a more troublesome relationship between print journalism and digital media.

With sites like Twitter, reporters can cover an event in real time. Reporters can clarify information in their articles. Reporters can even publish their original work themselves. Yet all of this is for naught if the reporter has no influence. A tweet does not matter if it is not seen by a considerable number of people or re-tweeted. Because audiences have unprecedented access to journalists, the journalist has found himself at the mercy of the audience’s whims. The journalist will deliver what the audience wants to see because that is what brings hits.

Each tweet written by the New York Times Company reaches over six million followers. Each of their Facebook status updates reaches over two million subscribers. In order for content on digital media to go viral, it must be controversial. Fact does not sell, but opinion does. After all, that is the purpose of sites like Twitter. However, digital media was not created to serve as a platform for the news. In fact, its initial purpose was quite the opposite. Digital media was created to allow people who could not convey their ideas through the traditional mainstream media to share their opinions with others. It provided a platform for subjective thought when other platforms focused on the objective. The subjective and objective platforms have since merged and this culture of interchanging fact and opinion has spread from digital media to print media.

As a result, the standards of journalism have been comprised: The State of Columbia did not verify the claims made against Governor Haley before it ran the story as its front-page headline.

The majority of Americans are influenced by either cable news or print journalism and the increasing shift of these institutions towards subjective journalism has drawn alarm. Critics like veteran New York Times reporter Gay Talese cautioned against journalism that spread beliefs instead of the facts to make those beliefs reality.

To combat these relaxed standards of journalism, a new group of journalists have emerged: the fact checkers. Fact checking originated to evaluate material that was written by someone who is not a trained reporter. The fact checker’s job is to conduct research on news stories, political speeches, and even other news organizations in order to assess the veracity of their statements.

Fact checking played a significant role in the 2012 presidential election by keeping both the Democratic and Republican campaigns in check. When done well, fact checking is an important tool for ensuring the public has access to correct information.

Fact checkers took away all credibility from the claim that Obama was not born in the United States. They also put to rest rumors that Romney has offshore accounts in the Cayman Islands. The fact checking industry is quickly growing. Every major news organization has a fact checking division within their infrastructure. And third-party fact checkers have also emerged.

The Annenberg Public Policy Center at the University of Pennsylvania launched FactCheck.org. In order to strive for objectivity, FactCheck.org receives independent funding from donations, and is both non-partisan and nonprofit. The conservative St. Petersburg Times started Politifact.com in 2007, which analyzes the accuracy of politician statements against a standard metric and even ranks politicians in order of their truthfulness. PolitiFact.com won a Pulitzer Prize for its work in 2009. These third-party organizations claim independence, yet this claim has often been debated. The Annenberg Public Policy Center receives funding from liberal think tanks, and FactCheck.org has been criticized for paying more scrutiny to Republicans than Democrats.

While fact checkers should be commended, fact checking itself has several shortcomings in ensuring accurate journalism. For example, the findings of a fact check are published after the misinformation has already spread. Correcting every manifestation of the original inaccuracy is nearly impossible in the age of the Internet. Fact checking findings are also published independently of their subject article and organizations need not direct their users to the fact check report.

Some of the claims that ought to be fact checked are too complicated or do not have a clear true or false answer. For example, during the 2012 presidential election, both campaigns frequently cited the increase in the federal budget deficit. It is difficult to calculate how much the federal budget deficit has actually increased because both campaigns use differing time periods for their calculations.

In the same campaign, fact checkers had a tricky time ascertaining the truth of the Obama campaign’s claim that the Republican Medicare plan proposed in Congress would cost seniors more than $6,000 per year. There was no simple answer because of the numerous hypothetical scenarios involved in the situation. Instead of giving a simple true or false, PolitiFact.com wrote a fact check that was 1,200 words long, including footnotes. Likewise, FactCheck.org wrote a fact check that was 1000 words long, too long to be read by the average voter.

Critics of fact checking argue that arguments in the media over the validity of outlandish claims draw more attention to the situation than there needs to be. It comes to a point that it does not matter if a false claim is true or not – all that matters is that it warrants a discussion.

One final problem with fact checking is its propensity to lead to idea checking. Idea checking is an inherent critique or even censorship of a speaker’s ideas and even the speaker himself under the guise of a fact check. The author of the idea check will often insert his own ideas into the supposedly objective report.

Idea checking has manifested itself most recently in a fact check done by the Associated Press on former President Bill Clinton’s speech at the 2012 Democratic National Convention in Charlotte, North Carolina.

In his speech, Clinton said, “When times are tough, constant conflict may be good politics, but in the real world, cooperation works better…Unfortunately, the faction that now dominates the Republican Party doesn’t see it that way. They think government is the enemy and compromise is weakness. One of the main reasons America should re-elect President Obama is that he is still committed to cooperation.”

The AP replied with, “From Clinton’s speech, voters would have no idea that the inflexibility of both is to blame for much of the gridlock. Right from the beginning Obama brought in as his first chief of staff Rahm Emanuel, a man known for getting his way, not for getting along.”

The AP’s first mistake is that it chose to “fact check” a portion of Clinton’s speech that was not factually based. In the first third of the quote, Clinton provides an opinion about the need for cooperation over conflict. He followed with an opinion held by himself and other Democrats regarding the Republican Party. He concludes by stating why Obama should be re-elected.

The Associated Press’ research does not examine whether cooperation actually works better than conflict during tough times, nor does not survey Republicans to see what they actually think. Instead it counters an argument Clinton does not even rhetorically make, that the Republicans are to blame for congressional gridlock. The Associated Press is not verifying Clinton’s statements – it is responding to his ideas with ideas of its own.

Clinton, in his DNC speech, goes on to refute an anti-Obama ad aired by the Romney campaign: “Their campaign pollster said, ‘We’re not going to let our campaign be dictated by fact checkers.’ Now that is true. I couldn’t have said it better myself – I just hope you remember that every time you see the ad.”

And the AP responded, “Clinton, who famously finger-wagged a denial on national television about his sexual relationship with intern Monica Lewinsky and was subsequently impeached in the House on a perjury charge, has his own uncomfortable moments over telling the truth. ‘I did not have sexual relations with that woman, Miss Lewinsky,’ Clinton told television viewers. Later, after he was forced to testify to a grand jury, Clinton said his statements were ‘legally accurate’ but also allowed that ‘misled people, including even my wife.’”

The AP critiqued a section of Clinton’s speech that should not be factually based, save for this first admission about what a Romney pollster said. Still, the AP does not attest to the validity of that statement. They do not confirm who said it and if that statement was even said. Instead, they analyze Clinton’s own character. When there were no facts to verify, the AP attacked the speaker.

This is not a partisan problem. Idea checking can also be found in the Associated Press’ “fact check” of Paul Ryan’s speech at the 2012 Republican Convention in Tampa, Florida.

Ryan says in his speech, “Obama created a bipartisan debt commission. They came back with an urgent report. He thanked them, sent them on their way and then did exactly nothing.” In their fact check the AP reported, “It’s true that Obama hasn’t heeded his commission’s recommendations, but Ryan’s not the best one to complain. He was a member of the commission and voted against its final report.”

Later in his speech, Ryan says, “The stimulus was a case of political patronage, corporate welfare and cronyism at their worst. You, the working men and women of this country, were cut out of the deal.”

The Associated Press responded, “Ryan himself asked for stimulus funds shortly after Congress approved the $800 billion plan, known as the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act. Ryan’s pleas to federal agencies included letters to Energy Secretary Steven Chu and Labor Secretary Hilda Solis seeking stimulus grant money for two Wisconsin energy conservation companies.”

The content of both AP reports may be true, and might have even been relevant for voters in the 2012 presidential election, but the reports were not fact checking – they were engaging in debate with the subjects. The Associated Press, an organization that is reputedly the m ost objective of news sources, along with other journalism institutions confuse objectivity with subjectivity.

If fact checking remains unchecked, the threat of idea checking will grow. Yet doing away with fact checking is not the solution. Instead, the current culture of journalism must revert to attitudes that were in force during journalism’s golden age: Fact and opinion must remain separate. This old idea is not at odds with today’s Internet culture.

Twitter is an extremely effective tool for promoting a news organization’s brand. Journalists can use hashtags and @replies to engage and connect with readers on a level that traditional platforms cannot allow. Social media is a great way to expand and grow journalism’s editorial facet.

Journalism is not supposed to tell the audience what it wants to hear. It’s not supposed to pander to what will get the most hits online or the most re-tweets on Twitter. Journalism is supposed to report the news, as Walter Cronkite would say, just the way it is.