Bye Bye Beijing

China’s recent activity in Africa goes beyond the mere muscle-flexing and oil-grabbing tendencies of an emerging global power. In the last five years, media reports of China’s growing presence in Africa have increasingly reinforced and intensified Western fears of an unrestrainable imperialist state. Articles brandishing headlines such as “China’s Economic Invasion of Africa” and “Africa: China’s New Backyard” depict Africa as the victim of China’s rapacious neo-imperialism. The Chinese government, however, denies these allegations of political colonization, rallying behind the official Chinese Communist Party foreign-policy slogan—“peaceful development.” Yet, contrary to the belief perpetuated by the mainstream media and Western states, Chinese influence in Africa is not likely to expand. And as the Chinese stay on the continent, perhaps starting to wane, the onus falls on African states to take advantage of the situation

China’s “Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence”—adopted in 1954 to mark the end of Sino-Indian disputes—clearly, but carefully states its intentions to support “sovereignty and territorial integrity, mutual non-aggression, and non-interference in [other countries’] internal affairs”. Broadening the Five Principles to apply to general international engagements, China largely uses its official foreign policy stance as a veil to justify questionable activities and deal-making in Africa. The policy’s explicit lack of an ideological agenda is an adept move allowing China to operate without appearing to directly challenge regional U.S. security interests, but also covertly promoting multi-polarity by endorsing sovereign rights for pariah states. Though China’s pronouncement of non-interference suggests that it merely intends to solidify trade relations and consolidate its “One-China” support base, Western nations view China’s growing economic activity in Africa and its impact on the continent with unease.

China’s recent activity in Africa goes beyond the mere muscle-flexing and oil-grabbing tendencies of an emerging global power. In the last five years, media reports of China’s growing presence in Africa have increasingly reinforced and intensified Western fears of an unrestrainable imperialist state. Articles brandishing headlines such as “China’s Economic Invasion of Africa” and “Africa: China’s New Backyard” depict Africa as the victim of China’s rapacious neo-imperialism. The Chinese government, however, denies these allegations of political colonization, rallying behind the official Chinese Communist Party foreign-policy slogan—“peaceful development.” Yet, contrary to the belief perpetuated by the mainstream media and Western states, Chinese influence in Africa is not likely to expand. And as the Chinese stay on the continent, perhaps starting to wane, the onus falls on African states to take advantage of the situation

China’s “Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence”—adopted in 1954 to mark the end of Sino-Indian disputes—clearly, but carefully states its intentions to support “sovereignty and territorial integrity, mutual non-aggression, and non-interference in [other countries’] internal affairs”. Broadening the Five Principles to apply to general international engagements, China largely uses its official foreign policy stance as a veil to justify questionable activities and deal-making in Africa. The policy’s explicit lack of an ideological agenda is an adept move allowing China to operate without appearing to directly challenge regional U.S. security interests, but also covertly promoting multi-polarity by endorsing sovereign rights for pariah states. Though China’s pronouncement of non-interference suggests that it merely intends to solidify trade relations and consolidate its “One-China” support base, Western nations view China’s growing economic activity in Africa and its impact on the continent with unease.

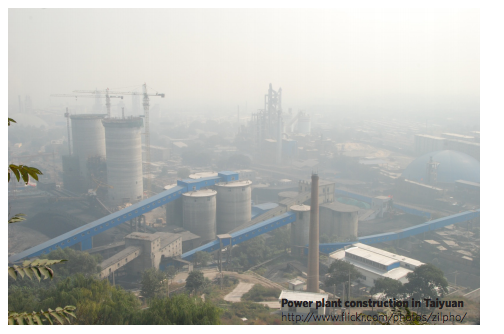

While swathed in assurances of “mutual development,” China’s foreign aid and economic policy is undeniably driven by its need for natural resources, with Chinese interests placed first and foremost and African concerns placed at a distant second. Already the world’s largest consumer of coal and steel, China increasingly depends on imported petroleum, aluminum, copper, and other raw commodities as its growing domestic consumer forces expand production. In the past 15 years, China’s mineral oil imports have more than quadrupled, with Africa supplying nearly one-third of China’s needs. China’s tremendous appetite for natural resources indicates and propagates its rapid economic growth.

But as China pursues an extended relationship with Africa, China will find its long-term objectives challenged by the effects of irresponsible deal-making and exploitative policies. Resistance to Chinese expansion in Africa may present itself in a combination of three fronts: pressures from an unsupportive international community, unstable environments of extraction and Chinese domestic discontent.

Regardless of its intent or future, the Chinese system of foreign aid is currently progressive in its comprehensive approach. Spanning human resources development to generous debt repayment plans, China’s aid packages appear to have potential to animate African development. China’s low-interest, prescription-free loans do not necessitate the market liberalization requirements that the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank stipulate, which means that funds can be directed toward more project-based, rather than capacity-building, development objectives. China has built much-needed railroads and mobile telephone networks in Kenya, Rwanda and Nigeria with varying success. Sweetening its deals, China also allows its trading partners to side step transparency and good governance requirements, unlike those stipulated in Western-dominated international aid institutions. According to the Pew Global Attitudes Project, African governments have responded enthusiastically, with approval ratings for China and Chinese actions reaching 71 percent across Sub-Saharan Africa, compared to 43 percent in the Western bloc. However, China’s politically indiscriminate and, at times, nontransparent partnerships with pariah states have increasingly provoked protests from the international community and human rights organizations.

Ultimately, China’s long-term objectives of trade expansion in Africa will be complicated, if not entirely subverted, by their short-term endeavors. An adroit massaging of its Five Principles conveniently justifies China’s operations within states heavily denounced for their human rights violations. China’s current relations with pariah regimes, such as those under Omar al-Bashir of Sudan and Robert Mugabe of Zimbabwe, visibly elicit dissatisfaction from organizations such as Human Rights Watch. China’s supplying of tanks, fighter planes, bombers, helicopters, and machine guns to Sudan’s Arab militia in Darfur chas sparked criticism from the United Nations. Though China has had ample experience operating outside of international norms, China’s increasing integration into the global economy will make it costly for the regime to extend its irresponsible economic collaborations. Furthermore, the United States is unlikely to watch idly while pariah regimes, propped up by Chinese aid, challenge its security and economic interests. For the time being, China seems prepared to weather damages to its reputation in the international community. Though the global community has, in a sense, patiently endured the idiosyncrasies of China’s foreign aid policy, there is little evidence that China will be able to continue its African policies in its current transgressive form uncontested.

Apart from eliciting international dissatisfaction, the strategy of peaceful development may ironically dismantle China’s natural resource projects in Africa, though it has largely allowed China to access regimes wary of liberal economic ideology and Western infringement on state sovereignty. China’s extractive activity depends on social and political stability, which enables the regular transport and production of resources. Though currently highly lucrative, China’s African policy will become increasingly difficult to sustain, as recurring civil instability provoked by pariah regimes disrupts the trading process.

Other aspects of Chinese “goodwill” have also proven problematic, and even unapologetically damaging. Chinese construction companies and contractors displace workers by the hundreds of thousands by stipulating unfair quotas that predominantly employ Chinese laborers. Pledging agricultural and medical transfers, Chinese technicians and doctors often exclusively use Chinese products, which are largely unaffordable and unavailable in rural areas. Chinese products have also flooded African markets, outcompeting local manufacturers across the Sub-Saharan production sectors and monopolizing local consumer markets. Dominating African markets, cheaply made Chinese goods ranging from hardware to sundries make it difficult for African consumers to access high-quality local products. In practice, China’s policy exhibits a lack of sensitivity shocking to both international and local constituencies.

China’s growing negative reputation in African states will, in the long run, fundamentally hamper its maneuverability in the continent’s industries and oil fields. Though news reports highlight the enthusiasm of “Africans” toward Chinese involvement, these reports almost exclusively refer to African governments and not the African populace. Dissatisfaction with inferior Chinese products and Chinese aid to pariah regimes effectively hinders civilian reform in social and political realms. Making little to no effort to curry favor with the African populace, China negotiates transactions with little concern of what effect their policies may produce in the civil sphere. Growing impatient with China’s backhanded policies, workers’ revolts against Chinese businesses in Zambia and Nigeria point towards a future of hostile and unproductive Sino-African relations. Ultimately, China’s dismissing attitude towards its African constituency may prove fatal for its trade interests.

Looming domestic dissatisfaction in China with the government’s increasingly hefty foreign aid commitments also complicate China’s dilemma. While China’s growing middle class endures job insecurity, stagnant living standards and low wages, the Chinese government publicly pledges an extension of its African foreign aid to reach $10 billion in soft loans and grants in the near future. China’s preoccupation with advancing Sino-African relations will be increasingly interpreted as domestic negligence. Though China’s reserve of $2.5 trillion can easily sustain China’s global ventures, a resentful domestic population will likely demand that the Chinese government take care of its own constituencies before bolstering a foreign market for increased Chinese investment. As its citizens grow increasingly conscious of their own economic inequality, Beijing will be hard-pressed to continue its current African policy. China will be recalled to address domestic problems before advancing international engagements.

Looming domestic dissatisfaction in China with the government’s increasingly hefty foreign aid commitments also complicate China’s dilemma. While China’s growing middle class endures job insecurity, stagnant living standards and low wages, the Chinese government publicly pledges an extension of its African foreign aid to reach $10 billion in soft loans and grants in the near future. China’s preoccupation with advancing Sino-African relations will be increasingly interpreted as domestic negligence. Though China’s reserve of $2.5 trillion can easily sustain China’s global ventures, a resentful domestic population will likely demand that the Chinese government take care of its own constituencies before bolstering a foreign market for increased Chinese investment. As its citizens grow increasingly conscious of their own economic inequality, Beijing will be hard-pressed to continue its current African policy. China will be recalled to address domestic problems before advancing international engagements.

While China will necessarily grapple with waning, or at least shifting, influence in Africa, African states are presented with a unique opportunity. Largely protected by Western counter interests and the hawk-eyed supervision of international organizations, Africa is unlikely to be subject to Chinese imperialism, at least not the imperialism of historic tradition. Moreover, African states stand in a position to benefit from China’s presence in their communities if they can reappropriate Chinese development strategies and successfully negotiate trading terms to maneuver in a global capitalist economy.

To Africa, China’s worth does not lie solely in its inclusive aid packages and infrastructure projects. Instead, the symbolic and historic Sino-African relationship possibly heralds prolonged gains for Africans by identifying a new conduit for economic growth. Sharing the same ideological transformation and accompanying developmental issues, China could act as a more viable model of development for African states than the highly formulaic, privatization- and liberalization-focused, top-down approach of the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund. Monitoring the modern Sino-African relationship from its launch in the early 1950s shows the correlation between Chinese and African economic growth. Surmounting similar socialist experiments and developmental roadblocks, China and many African states have exhibited impressive leaps in their yearly gross domestic product since their initial trading agreements.

China’s approach of instituting citizenexchange programs, protectionist trade barriers and public-private sector partnerships, stands a better chance of creating sustainable, autonomous trading and production institutions in Africa. By studying the Chinese model of development as an alternative to the West’s liberal “Washington Consensus” policies, African states can benefit from China’s similar experience in liberalizing its economy. Increased communication between African and Chinese governments could bring systematic, coordinated dissemination of technological and agricultural knowledge that would help production sectors across African states. Particularly, Chinese agricultural practices, revealed through studies conducted by the University of Stellenbosch in South Africa, have the potential to revolutionize African smallholder farming by introducing superior plant breeding techniques, specified fertilizers and drip-irrigation systems. By implementing Chinese research on plant genetics and soil composition and transferring agricultural technology, African states could dramatically improve food quality and harvest.

Though China’s involvement in Africa is far from over and far from “mutually beneficial,” African states still stand to gain from China’s presence in the continent. Media reports dramatize China’s hold on the continent—China’s grip is neither pervasive nor absolute. However, the media’s sensationalizing of Sino-African relations inflicts the most damage—not through misinformation but through misconstruction. Exploiting the profitable trope of victim-aggressor dynamism, reports illustrate an antagonistic China encroaching upon a passive Africa. This context effectively disenfranchises and demeans the African position, and perpetuates earlier debates of centrism and peripherialism. African states can possess a significant amount of control in its relationship with China. Before Africa can reclaim its position at the global negotiating table, dialogue surrounding Sino-African relations must not preemptively discount the African prerogative and the continent’s sovereignty. In anticipation of weakening Chinese influence, African governments and their constituencies would do best by capitalizing on this moment of informational and technological exchange and accepting Chinese aid with a cautious eye.