Change Japan Can Believe In

“This is a historic election,” pronounced the morning newscaster. “This country is going to change,” announced a political leader. He posed in front of campaign posters that read, “This is change we can believe in.” To an American audience, these phrases would immediately conjure up images of President Barack Obama’s election in November 2008. But here they referred to Japan’s lower house elections on August 30 2009, leading to Yukio Hatoyama’s victory on September 16 as the new prime minister.

I heard the first quote at home in Tokyo on the day of the elections. The Liberal Democratic Party (LDP), which has governed Japan since 1955, appeared, for the first time, to be seriously threatened by its opposition, the Democratic Party of Japan (DPJ). The DPJ is to the left of the LDP, but has never succeeded in getting a majority in the lower house.

While Taro Aso, the LDP then-prime minister, displayed his infamous smirk, Yukio Hatoyama, representative of the DPJ, approached citizens with his slogan, Seiken Koutai—Regime Change. Other parties that strove to oust the LDP had used similar slogans, but voters connected with this one. The DPJ used this phrase with unprecedented boldness, shaking the public’s half-century-old devotion to the LDP.

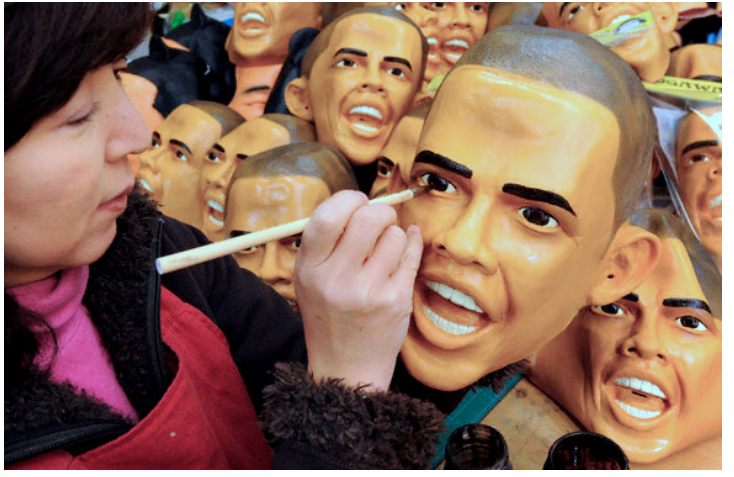

It was not an accident that the DPJ borrowed much of this rhetoric straight from President Obama’s campaign playbook. During President Obama’s campaign, Japanese Obama impersonators became popular entertainers. Coincidentally, a port city named “Obama” cheers for the American president for all his accomplishments to this day. With a similar effect, CNN’s report of the Japanese elections also noted, “Hatoyama touted a Barack Obama-style message of change.”

“This time, it’s really not about whether or not the DPJ will win,” one Japanese man said to me. “It’s a question of by how much the DPJ will win.”

Although newsreels anticipated that the DPJ would win the election, the degree of the victory was astounding. The party won 308 of the 480 seats in the parliament’s lower house, reducing the LDP to a significant minority of 119 seats. (The DPJ already held a majority in the upper house.)

“People kept saying, ‘You’re going to be a part of this historical change,’ and of course this gets people excited,” said Sayuri Shimoda, a Columbia College senior who was able to participate as a Japanese citizen. Shimoda also attended Obama’s inauguration last fall in Washington D.C. “[In D.C.] You could really feel people’s optimism that things are actually going to change…” but, Shimoda added, “I don’t see things changing that drastically in Japan.”

CHANGE AS REJECTION Seiken Koutai was the ideal way for LDP members disappointed in the lack of prime ministerial stability to signal their disapproval. “In America, change is perceived as a good thing,” Barnard senior Mari Mizoguchi says. “But for the Japanese people, change means something different. In this case, it’s about being different from the LDP.”

Many Japanese people were frustrated that, since 2006, every year has been another game of musical chairs among LDP representatives for the prime minister seat. After Junichiro Koizumi finished his third term in September 2006, Shinzo Abe took over—the first prime minister of Japan to be born after World War II. Nationalistic and classically conservative, Abe made significant political reforms, the most famous one being his decision in January 2007 to upgrade the defense agency to an actual ministry. But eight months later, he suddenly resigned due to poor health, with an approval rating below 30 percent. Yasuo Fukuda was then elected, but resigned a year later. His last words to the public were, “I am different from you.” Then came Prime Minister Aso Taro in 2008, the former Minister of Foreign Affairs, who wanted to fund a manga museum, using the national budget at a time when Japan was running a high deficit. Enough was enough.

CHANGE AS ALTERNATIVE “This election marked the end of the postwar political system in Japan,” said Professor Gerald Curtis of the Columbia University Political Science department. Professor Curtis has published many books on the Japanese political system and currently teaches a course on Japanese politics. “There’s no going back to what Japanese politics was prior to August 30.” Curtis noted that the DPJ’s fresh approach changes Japan’s economic and political priorities.

To name one of the most controversial policies, the DPJ plans to give approximately $130 every month to families with children under 15, in order to combat the low 1.3 child per family birthrate. “We would like to engineer a huge policy shift to change Japan into a country where society as a whole supports childrearing,” says DPJ Secretary General Katsuya Okada of what is now known as the “child allowance program.” The DPJ also plans to eliminate highway tolls all over the country in order to increase domestic consumption and make it easier for domestic businesses to transport goods to the different regions. Interestingly, according to a poll conducted in Kyushu, a southern region of Japan, 54.7 percent of big businesses strongly disapprove of this plan.

The left-leaning newspaper Asahi Shimbun revealed that a total of 83 percent of respondents expressed uneasiness about DPJ’s plans. 55 percent expressed disapproval of the childhood allowance program while a whopping 67 percent expressed disapproval of the highway toll elimination plan. Another paper, Sankei Shimbun, despite its conservative perspective, showed that 65.4 percent disapproved of eliminating highway tolls.

On the other hand, the approval rating for Hatoyama’s cabinet skyrocketed to 75 percent by mid-September. It seems incoherent that the Japanese people would vote for a party whose major domestic policies garnered such high disapproval ratings. Curtis says, “The DPJ is changing Japan’s economic priorities.” Change means alternative, but is it a better or worse alternative? While data shows that most Japanese people see the DPJ’s plans as a worse alternative to what the LDP had done, it will be interesting to see whether the DPJ can actually achieve these promises and prove itself to be the better alternative.

Americans interested in U.S. foreign policy should keep their eyes out for the DPJ’s stance on the longstanding U.S.-Japan relationship. Hatoyama has made it clear that he and the party are seeking a “more equal relationship” with the U.S. Japan may be the second biggest economy next to the U.S. and its strongest economic partner. Under Japan’s postwar constitution, Japan “cannot use force as means of settling international disputes,” and under the San Francisco Peace Treaty of 1951, the U.S. military serves as Japan’s main source of national security, which means U.S. military bases are scattered all across the country even today.

Hatoyama is not proposing to change the Japanese constitution in any way. So what does it mean for him to want a “more equal relationship” with the U.S.? “The DPJ is much more determined to not let the military issues drive the alliance,” says Curtis. “[Hatoyama and his cabinet] will change the relationship with regards to the American troops in Okinawa.”

The issue of U.S. bases in Japan is not as prominent on the mainland. But on the Okinawa islands, located in the southwestern region very close to Taiwan, this is still a major concern. This archipelago suffered not only the most ferocious on-land battle during WWII, but was also under U.S. military occupation for 27 years, 20 more years than the occupation of the rest of Japan. During this long period of time, the U.S. established fourteen bases that take up twenty percent of the small island. The tragic memory still deeply rooted in Okinawan society and the numerous U.S. bases suggest that the occupation has not actually ended. When I drove through Okinawa last summer, I always had a military base in my peripheral vision. “It’s about time to reduce the huge American presence in Okinawa,” says Curtis.

In 2006, the LDP and the U.S. agreed on a U.S.-Japan realignment pact that includes expanding the Futenma Air Base in Okinawa, home to about 4,000 U.S. Marines as well as a part-time United Nations air facility. Hatoyama wants the U.S. to consider a renegotiation, partly for economic reasons, but also as a step to establishing a “more equal relationship.” Hatoyama wants to move Futenma off the island completely and eventually work on decreasing the number or size of the other bases in Okinawa. Another Pacific island, perhaps the U.S. territory of Guam, may have to take on the burden. In September, Secretary of State Hillary Clinton suggested that while “Washington sees the 2006 agreement as the basis for the realignment,” it is “ready to continue negotiating on that matter.”

CHANGE AS A TESTING PERIOD “What’s the first thing that pops up in your mind,” I asked undergraduates and graduate students at Columbia who participated in the Japanese elections, “when you hear Seiken Koutai?”

Students at SIPA who have experience working for the Japanese government split into two groups, one uncertain about the DPJ’s ability to govern and the other hopeful and excited about change. Those in the latter group, along with Mizoguchi, believed that this regime change is “a trial period for the DPJ.”

Ryu Murakami, a Japanese fiction writer who wrote on the Japanese elections for the New York Times last month, suggested that the Japanese people are “merely experiencing the melancholy that any child goes through as adulthood approaches.” Japan is fully aware that it is changing, but uneasy and uncertain about actually going through it.

Support is one thing, but optimism is another. Japanese students have no idea how this new, inexperienced party will handle unexpected situations, but we do know that the DPJ is serious about changing Japan. After years of LDP’s failures, perhaps it is about time that the DPJ takes a shot at fixing issues like the economy and the low birth rate. Regardless of whether these changes will succeed, “Japan will change,” says Curtis. “And I see it as a good thing.”