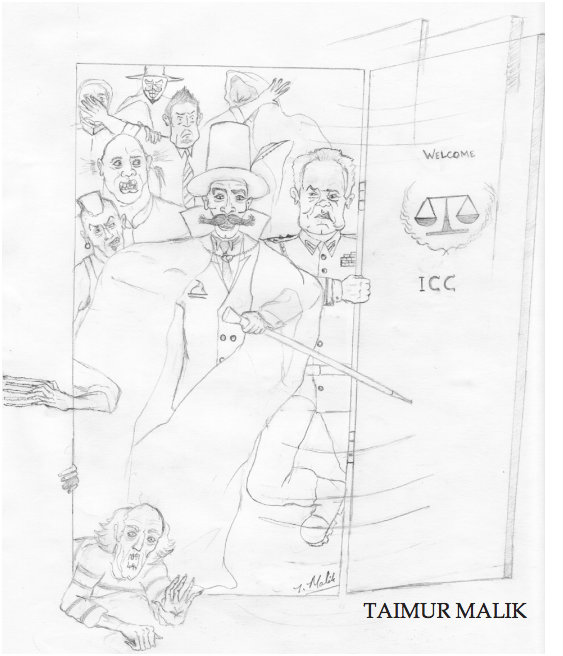

Universal Jurisdiction and the ICC’s Growing Global Sway

On May 6, 2002, the Bush Administration took the unusual action of ‘unsigning’ an international treaty. Equally unusually, Bill Clinton had signed this treaty on his last day in office more than two years earlier. The treaty in question was the Rome Statute, the founding document of the International Criminal Court (ICC).

The debate within America over the ICC mirrors a larger discussion underway in academic and political circles across the world. Does it go too far? Not far enough? In academia, one school of thought maintains that the ICC represents the end of the Westphalian order, perhaps even the “onset of global governance.” Political supporters such as Kofi Annan believe the establishment of the Court to be “a historic moment … a giant step forward in the march towards universal human rights and the rule of law.” Other scholars contend that the Court is essentially irrelevant. Spyros Economides, an International Relations and European Politics lecturer at the London School of Economics, has argued that the Court’s independence and capacity to act have been “sacrificed… at the altar of state sovereignty.” And in some diplomatic circles, critics like Henry Kissinger argue the other extreme —that the ICC is too powerful.

On May 6, 2002, the Bush Administration took the unusual action of ‘unsigning’ an international treaty. Equally unusually, Bill Clinton had signed this treaty on his last day in office more than two years earlier. The treaty in question was the Rome Statute, the founding document of the International Criminal Court (ICC).

The debate within America over the ICC mirrors a larger discussion underway in academic and political circles across the world. Does it go too far? Not far enough? In academia, one school of thought maintains that the ICC represents the end of the Westphalian order, perhaps even the “onset of global governance.” Political supporters such as Kofi Annan believe the establishment of the Court to be “a historic moment … a giant step forward in the march towards universal human rights and the rule of law.” Other scholars contend that the Court is essentially irrelevant. Spyros Economides, an International Relations and European Politics lecturer at the London School of Economics, has argued that the Court’s independence and capacity to act have been “sacrificed… at the altar of state sovereignty.” And in some diplomatic circles, critics like Henry Kissinger argue the other extreme —that the ICC is too powerful.

The truth probably lies somewhere in the middle. It is unlikely that the ICC will dramatically or directly change international relations. At the same time, the Court is not irrelevant. The ICC’s greatest impact will spring from its “secondary functions,” that is, the ways in which the ICC will influence state behavior indirectly.

The main impact in this regard will be to increase both the quantity and the quality of war crimes trials. This includes—indeed primarily refers to—war crimes trials not conducted at the ICC. In 1998, the Coalition for the International Criminal Court, an umbrella organization of NGOs campaigning for the ICC’s establishment, argued that “…the ICC will cause the greatest strengthening of national prosecution of crimes against humanity.”

There are three fundamental reasons for the indirect effects of the ICC. The first concerns why more trials will happen: the ICC allows for an independent prosecutor who can initiate trials absent authorization from a state or the Security Council. The second is that the trials will likely not be conducted at the ICC due to ‘complementarity—meaning that the ICC’s jurisdiction is not superior, but complementary, to national jurisdictions. Any state can take over an investigation commenced at the ICC, and the Court cannot pursue a case already being investigated by a domestic court. And the third—why the trials would reach a higher standard of impartiality, transparency, and efficiency—derives from the Rome Statute’s authorization of the ICC to retain control of any investigation or prosecution if it concludes the State in question is “unable or unwilling genuinely” to conduct the trial.

The second point, complementarity, has not elicited as much controversy as have the first and third. For instance, the Bush Administration’s opposition to the ICC is largely based on its concerns over the prosecutor’s power and the ICC’s authority to determine domestic judicial ability and effectiveness.

More Trials The independence of the prosecutor allows for high levels of access to the ICC: any individual, organization or state can refer situations to the prosecutor for investigation. Consequently, the number of cases likely to be pursued by the ICC is higher than would be the case if only states had referral rights. This point is evidenced by comparison with other international courts, especially the European Court of Justice (ECJ) and the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR). Where the access levels are low, the number of cases is low; where high, the number of cases is high.

One should reasonably expect to see a greater number of investigations by the ICC than if there was no independent prosecutor. Most of these investigations will likely be initiated by the prosecutor at the request of individuals and organizations, as has been the case with ECJ and ECHR, not by states. Although these investigations will probably be taken over by national courts, under the complementarity system, the net result is still the same: there will be more war crimes trials.

It should also be noted that the mere possibility of the prosecutor’s initiating an investigation may pressure states into commencing war crimes trials, either nationally or at the ICC. Indeed, the first cases in the history of the ICC resulted from such pressure. The Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) referred the violence in Ituri to the ICC for investigation only after the Prosecutor threatened to initiate an investigation himself, and the DRC acted to avoid the public embarrassment of being investigated by the ICC against its will.

Fairer Trials Prior to the Rome Conference, several states and NGOs were concerned that the complementarity system would make the ICC self-defeating: it would never actually try a case because states would take over cases every time the ICC initiated them, shielding perpetrators. Eventually, states granted the ICC the power to hold trials at the Court, should a state be “unable or unwilling genuinely to carry out the investigation or prosecution.” The specific criteria for making such a determination are laid out in Article 17 of the Rome Statute. These criteria will be further clarified by precedents set by the ICC as it hears more cases.

Since it is the ICC, not states, which assesses state ability or unwillingness to bring defendants to justice, the Court has de facto judicial review powers. One can expect that if the ICC was to determine a state “unable or unwilling” to conduct a fair trial, it would come as a significant embarrassment to that country. In order to avoid that embarrassment, states are more likely to conduct more transparent and more impartial trials.

Conclusion While the ICC may not have a significant or direct impact on international relations in its primary functions, it will likely have a strong, if indirect, normative impact over time.

More war crimes trials will likely take place than would absent the ICC’s independent prosecutor. Even if such trials are not conducted at the ICC, the Court could still be said to make a significant impact. The first prosecutor of the ICC, Luis Moreno-Ocampo, noted, “As a consequence of complementarity, the number of cases that reach the Court should not be a measure its efficiency. On the contrary, the absence of trials before this Court, as a consequence of the regular functioning of national institutions, would be a major success.” Second, the ICC will exercise a de facto judicial review function. This will pressure states to adopt standards of transparency, impartiality and efficiency determined by the ICC itself.