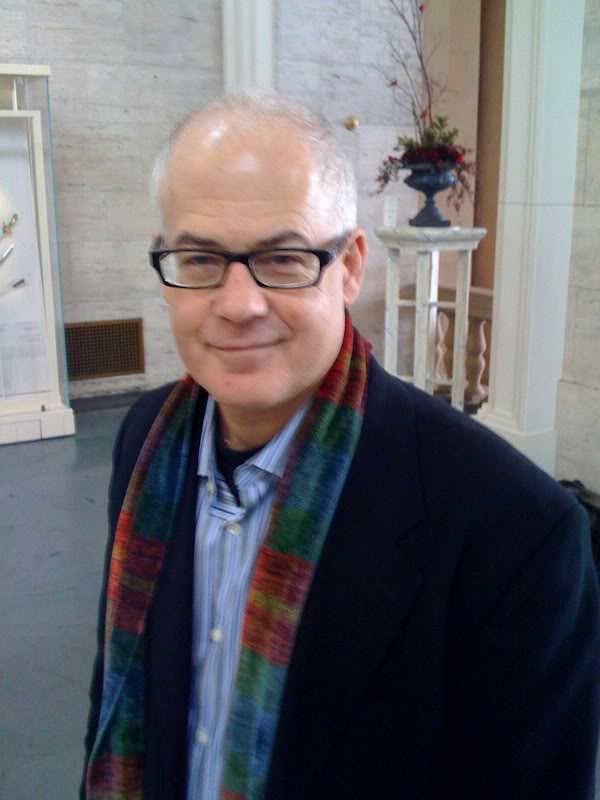

Interview with Bruce Robbins

Bruce Robbins is a professor of English and Comparative Literature at Columbia. His most recent book is Upward Mobility and the Common Good: Toward a Literary History of the Welfare State (Princeton, 2007). Florence Lui and Mark Krotov spoke to him about contemporary literature and its production, promotion, translation, distribution, and consumption, as well as the legacy of the culture wars of the 1990s.

On the literary marketplace:

“Capitalism is a bad thing to be distinguished from the market. If there’s a market for Karl Marx’s work, it will be sold. The market does not exclude things that are subversive—even subversive to itself.”

Bruce Robbins is a professor of English and Comparative Literature at Columbia. His most recent book is Upward Mobility and the Common Good: Toward a Literary History of the Welfare State (Princeton, 2007). Florence Lui and Mark Krotov spoke to him about contemporary literature and its production, promotion, translation, distribution, and consumption, as well as the legacy of the culture wars of the 1990s.

On the literary marketplace:

“Capitalism is a bad thing to be distinguished from the market. If there’s a market for Karl Marx’s work, it will be sold. The market does not exclude things that are subversive—even subversive to itself.”

“The contradiction is, if you want something to sell, you need distinctive characteristics, on a purely pragmatic level. Ben Okri, in writing African novels, has been really different from other novelists. And he’s been a market success.”

******

On globalization of literature: “Literarily speaking, I’m not sure the world market today is going through anything substantially different from what the market went through in the 19th century with regional literature. Walter Scott of Scotland, for example, sold to an English, Anglophone readership. He can be seen as something of a traitor to the vulnerable Scottish population he is writing about, translating it into something an English readership will understand. At the same time, the English readership is vulnerable to be seen as traitorous to an English public sphere.”

“There is a structural possibility for any regional writer to mediate … it is in the nature of the task of the metropolitan writer to mediate—writing between a metropolitan readership and a group seen as distinct.”

“We’re getting a world scale version of the same thing, except that national borders versus regional borders mean there is the introduction of a different language.”

“But given advances in transportation—is the distance real? What’s distance, exactly?”

******

On the possible homogenization of literature as it becomes globalized: “A number of questions [come] from a concern that the new market of world literature involves too much flattery of the prejudices and complacencies of the American market. Things are being produced for that market and a kind of homogenization results … I think these are good things to be worried about.” “The funny thing about [a January Magazine interview with novelist Kazuo Ishiguro, in which he states, “I stop myself writing certain things because I think, for instance, that it wouldn’t work once it’s translated out of English.”] is: it’s a metropolitan writer worrying about it, which suggests there is a similar pressure on people everywhere.”

******

On the translation issue: “There is an Italian expression—traduttore, traditore—which translates to, “the translator is a traitor.” There’s no such thing as a translation without betrayal. But it is an argument against translation? I don’t think so.”

“I’m content with a processural model where inevitably you get things wrong, but as long as there’s follow-up, there is a possibility of correcting your errors.”

“In the Museum of Contemporary Art in Sydney, there is a video playing in perpetuity called Barbecue Area, in which aboriginals discover an all-white Australia: “I hereby name this Barbecue Area.” A whole lot of translation starts with barbecue area. It doesn’t stay there, though.”

******

On literary celebrity: “Is it a question of capitalism, or the dynamics of celebrity? The Latin America boom in the 60s, for example—definitely not just Marquez. It doesn’t seem to me that the nature of celebrity or distribution means there’s only very limited room for authors from country x or y. When people get excited about Marquez, they will be more willing to read Allende, etc.”

“The frustration is that there are so many more people that are good than the market will pay attention to. Perhaps the real problem is that we don’t read as much as we used to.”

******

On university vs. market canonization: “The university has a trickle-down effect, as it did with Toni Morrison’s Beloved, in which college-educated students became high school teachers who taught it. The power the academy has is only relative, but it does have some.”

******

On the legacy of theculture wars: “They charged that there is a zero-sum game of canonization. For something that is added, something comes out (i.e. “No one teaches Shakespeare anymore, only Toni Morrison”). That turned out not to be true.” “We no longer read Longfellow, but in the 19th century, no one read Dickinson or Melville. Canons change and are in flux all the time.”

“The culture wars are not really over, but have subsided for now. One cynical explanation is that this is a softening-up operation to prepare for a Reagan-style systematic defunding of public education. To make the public think higher education is not good, propel them to pull money back, make it dependent on private funding.”

“These were the same years in which CUNY system had huge cutbacks, as did library systems on which young scholars totally depend. The pressure to work on something that a larger number of people outside the academy will want to read is greater.”