Invisible Children

Rampant apathy and cynicism. Growing civic disengagement. Hedonistic individualism. These accusations have often been leveled at our generation of students. The lack of traditional engagement by the 18-24-year-old cohort has been seen as the end of student activism. But these criticisms are blind to the diversity and subtle power of the student action happening today.

Unlike activism during the Vietnam War, there is no unifying cry, no single message. And methods have changed. Forty years ago, the violent takeovers of buildings, paralyzing strikes and destruction of property were visible forms of protest used by students to incite response from the outside world. Today’s student activists, more legally and operationally savvy, use quieter methods whose power often goes unnoticed. Protests still provide one vein of action, but administrators have seen a marked rise in the willingness of activists to comply with university security and rules. Students use authorized channels to provoke change on the campus, as well as national and international, level. Their strategies are quieter, but make no mistake: methods of engagement by today’s college students make for powerful political action.

Rampant apathy and cynicism. Growing civic disengagement. Hedonistic individualism. These accusations have often been leveled at our generation of students. The lack of traditional engagement by the 18-24-year-old cohort has been seen as the end of student activism. But these criticisms are blind to the diversity and subtle power of the student action happening today.

Unlike activism during the Vietnam War, there is no unifying cry, no single message. And methods have changed. Forty years ago, the violent takeovers of buildings, paralyzing strikes and destruction of property were visible forms of protest used by students to incite response from the outside world. Today’s student activists, more legally and operationally savvy, use quieter methods whose power often goes unnoticed. Protests still provide one vein of action, but administrators have seen a marked rise in the willingness of activists to comply with university security and rules. Students use authorized channels to provoke change on the campus, as well as national and international, level. Their strategies are quieter, but make no mistake: methods of engagement by today’s college students make for powerful political action.

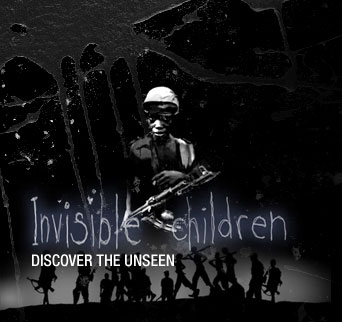

Take Invisible Children, the brainchild of three amateur filmmakers. After they “hopped on a plane to Africa,” three students from the University of Southern California’s film school and University of California’s School of Design chronicled the moving story of night commuters and child soldiers in Northern Uganda. Millions of hits from college students later, the cause is a crucial issue for many NGOs, and has captured the attention of Washington. Columbia’s own InterVarsity Christian Fellowship (IVCF) has partnered with World Vision, a Christian humanitarian organization, to provide immediate assistance to the area most affected by the two-decade conflict in Uganda. Inspired by the documentary, and World Vision’s Children of War Rehabilitation Center in Gulu, Uganda, IVCF contacted World Vision and committed to raise a minimum of at least $10,000 for the town. With over 36 child sponsorships and $40,000 raised in the past year, Columbia’s contribution is providing long-term care for children and families affected by the AIDS crisis. “Our initiative to sponsor this community has expanded from Columbia to include NYU, FDU, Princeton, Rutgers, Baruch and St. John’s Universities,” says Columbia College senior Jonathan Walton. Invisible Children is just one example of student activism drawing attention to little-known causes more effectively than top-down movements.

Ironically, current student activism often goes unacknowledged, but its very power lies in its innovative approach to “going public.” Growing up with the internet available on their home computers, students can instantly draw awareness to their causes through Facebook, MySpace, and chain emails. With just a dozen cell phones and the know-how of a few web designers, groups can lobby organizations and elected officials on the steps of Low Library or across the world. With lowered barriers to communication, causes can be broadcast to a wider audience than ever before. “Going public” is the greatest tool of contemporary activists. Using the media and other external pressures, activists can force the hand of administrators, corporations, and politicians who fear negative backlash from public attention. By 1997, 46% of college campuses reported the use of going public as a tactic of student protest. As Diana Alvarado, a research associate from the Office of Education and Diversity Initiatives, explains, “Through email networks, listservs, and discussion groups, students are more informed than ever and can very quickly discuss, debate, and organize nationally around a variety of issues.” The effects of these methods are often ignored, but there’s no doubt that students creatively using technology and media have incited significant change.

And it’s not just the methods of engagement that have changed; the very nature of student activist causes has evolved as well. Students can create niche markets that call attention to little-known causes. Discussions about crises in Sudan or Israel and Palestine are now supplemented by awareness of less publicized struggles, like aid for struggling Northern Ugandan villages. For instance, twenty-two year old Alexander McLean recently won a philanthropy prize in the United Kingdom for his “African Prisons Project,” a program aimed at improving dilapidated prisons in East Africa. New technology is not just a powerful medium; by casting a searching eye on new issues, it has transformed the very substance of student activist causes.

There is a strong argument for the long-term benefits of grassroots student activism. Students drawn in at a critical point of development discover non-traditional methods of civic engagement. Grassroots movements have the potential to draw in members of all socioeconomic, racial, and political groups. The commitment to these causes often continues even after college ends, when our access to financial and informational networks expands further. The strong operational skills gleaned from student activism instill the confidence and prowess to combat inequalities in the future. In their post-collegiate lives, former student activists may join organizations like MoveOn.org or more intimate groups to address pressing issues. While top-down movements may have the power of regulation and compulsory participation, the work of student activism infuses new graduates with a sense of realistic idealism.