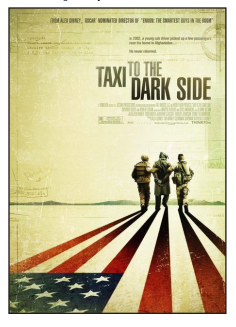

Film Review: Taxi to the Dark Side

Having directed Enron: The Smartest Guys in the Room (2005) and having served as the Consulting Producer for Who Killed the Electric Car? (2006) and Executive Producer for No End in Sight (2007), Alex Gibney has found a formula to refresh the politico-documentary genre and penetrate Hollywood’s mainstream distribution. But even that penetration is merely a scratch. Taxi made its official debut at the 2007 Tribeca Film Festival. Since then, it has been distributed to 16 theatres across the country, grossing well under $100,000 at the box office. Given that Taxi was released on the heels of the success of No End in Sight, (which made approximately $1.5 million) and that Gibney had a hand in both, the two films invite comparison. Taxi to the Dark Side strikes this viewer as No End in Sight-lite. For better or for worse? It’s a matter of personal opinion.

In his sophomore attempt as a documentary director, Gibney examines the torture practices of the United States in Afghanistan, Iraq and Guantanamo Bay. The film opens with the image of a warm, orange sun setting beyond the hills and a single car driving through a halcyon desert: it is 2002 in Afghanistan, at the start of the debacle we now know as the “War on Terror.”

Having directed Enron: The Smartest Guys in the Room (2005) and having served as the Consulting Producer for Who Killed the Electric Car? (2006) and Executive Producer for No End in Sight (2007), Alex Gibney has found a formula to refresh the politico-documentary genre and penetrate Hollywood’s mainstream distribution. But even that penetration is merely a scratch. Taxi made its official debut at the 2007 Tribeca Film Festival. Since then, it has been distributed to 16 theatres across the country, grossing well under $100,000 at the box office. Given that Taxi was released on the heels of the success of No End in Sight, (which made approximately $1.5 million) and that Gibney had a hand in both, the two films invite comparison. Taxi to the Dark Side strikes this viewer as No End in Sight-lite. For better or for worse? It’s a matter of personal opinion.

In his sophomore attempt as a documentary director, Gibney examines the torture practices of the United States in Afghanistan, Iraq and Guantanamo Bay. The film opens with the image of a warm, orange sun setting beyond the hills and a single car driving through a halcyon desert: it is 2002 in Afghanistan, at the start of the debacle we now know as the “War on Terror.”

For a contemporary political documentary filmmaker, the primary challenge is to temper the dry interview format by bringing the human connection to the surface of the material. Add the audience’s War in Iraq-fatigue and the justified but tired use of the Bush administration as a scapegoat, and one is left with a very narrow space to navigate as a documentary filmmaker of the “War on Terror.” Thank goodness that it was Gibney—experienced but fresh—who made this Iraq War movie, and not anyone else.

Gibney attempts to tackle the issue of torture by focusing on Dilawar, a taxi driver in Kabul, Afghanistan. Dilawar was detained at the Bagram Air Base in December 2002 and died five days later in U.S. custody—a death marked as a homicide by a U.S. military official. The film seeks to ascertain how and why this Afghan civilian died while in U.S. custody. The official production plot synopsis describes the film as a “documentary murder mystery,” and the way this particular conceit works in the film is no more effective than the cheesy marketing ploy that describes it. The film opens with footage of a Kabul taxi driving through desert and it closes with footage of an old-fashioned taxi driving on the calm, tranquil Georgetown streets of D.C.; other than that, the taxi ride goes nowhere. However, Dilawar was chosen not only because he was the second detainee to die in U.S. custody after the start of the “War on Terror,” but also because the reason for his detention is still unclear.

As expected, the film examines the conduct and policy of torture in the Bush administration’s “War on Terror.” “The Dark Side” is taken from a 2001 quote by Vice President Dick Cheney on Tim Russert’s Meet the Press: “We also have to work through … the dark side … it’s going to be vital for us to use any means at our disposal, basically, to achieve our objective.” Gibney structures his documentary around a few narrative strains that demonstrate American responsibility: the history of the torture tactics, the failings of the military chain of command, the evolution of legal interpretations of torture, and even the complicity of the American public. Gibney depicts the context of post-9/11 America as a tainted petri dish of failings and injustices; as Spc. Damien Corsetti states in the film, “You put people in a crazy situation and they’ll do crazy things.”

These narratives coalesce to return viewers to one of our most elementary ethical ideas: we are each responsible for our individual actions, as a citizen, a soldier, or as an elected policymaker. Unfortunately, the reality of contemporary American life is not the third-grade classroom, where we were first introduced to that principle. In the international arena, as American citizens, we are one body in the form of a nation. When a few people commit atrocities, the nation suffers. In the case of post-9/11 American torture, the suffering may be yet to come: almost every interviewee expresses fear and expectation of retaliation as a direct result of U.S. abuses of thousands of detainees.

Gibney does not end his provocative film with a firm conclusion. However, his closing sentiment—what can be inferred to be his inspiration for the documentary—is possibly the greatest feat of this movie. Right before the credits, Gibney shows a clip of his father, Frank, who worked as an interrogator during WWII and the Korean War. Frank cites his flagging faith in the American government as tied to the fall of American reverence for the rule of law. What set the United States apart and ushered in its ascent as the most powerful nation in the world in the twentieth century, he says, was the very respect for the rule of law ingrained in American values. Now that this is clearly gone from the American fabric, at least at the level of the government, the future of America seems quite dim. It may have taken the depiction of our darkest recent abuses for us to recognize just how deeply this element of the American Dream has eroded. In this respect, Taxi’s win at the 2008 Academy Awards for Best Documentary Feature seems promising. Or, the realization may still be coming—as the box office numbers for this film may indicate.

Taxi to the Dark Side is a film that could easily have fixated on, and mired itself in, the spectacle of torture itself. But it was a relatively easy hour and forty-six minutes to sit through, contrary to my initial reservations about seeing the film in a theatre instead of waiting for it on Netflix. The depictions of torture were not gratuitous—most were still photographs or reenactments to show how things were done. The strength of No End in Sight lay in the fact that the film was effectively an academic paper commuted to the screen; the power of Taxi Drive to the Dark Side is the way the movie offers the best of all the elements of a politico-documentary film—a clear yet sophisticated organizational structure, a pertinent group of interviewees, and skillfully edited photos and video shots. The question left is: should Gibney have offered more of a hook to lure Americans into seats?