Generation Blowhard

Again, again, the accusatory finger; the angry bark, the grimace of rage. These are the sacraments at the church of Bill O’Reilly, host of Fox’s top-rated O’Reilly Factor, a show that attracts 2.2 million of the faithful on a daily basis. O’Reilly is just one of a generation of emotional commentators, that is, pundits, who have been charged with transforming political analysis into emotional entertainment. He has been dogged by accusations of misinforming, spreading propaganda and outright mythmaking in his commentary—and he also helms the most popular show in cable news.

Rhetorically speaking, the pundit is a strange animal: a kind of crippled orphan using the language of a priest, a self-righteous uncle and a used car salesman combined. Someone who limps toward emotional statements, not newsworthy conclusions. But subjective commentators have been around since news existed for commentators to comment on. What is so wrong with this particular species of pundit? Their language is emotional, their popularity troubling, their arguments simplistic and infantilizing. They have personalized the public sphere by making their shows into personality- driven universes with similarly subjective truths. And they are, above all, the captains of what David Foster Wallace calls a “peculiar, modern, and very popular type of news industry, one that manages to enjoy the authority and influence of journalism without the stodgy complaints of fairness, objectivity, and responsibility that make trying to tell the truth such a drag for everyone involved.”

Again, again, the accusatory finger; the angry bark, the grimace of rage. These are the sacraments at the church of Bill O’Reilly, host of Fox’s top-rated O’Reilly Factor, a show that attracts 2.2 million of the faithful on a daily basis. O’Reilly is just one of a generation of emotional commentators, that is, pundits, who have been charged with transforming political analysis into emotional entertainment. He has been dogged by accusations of misinforming, spreading propaganda and outright mythmaking in his commentary—and he also helms the most popular show in cable news.

Rhetorically speaking, the pundit is a strange animal: a kind of crippled orphan using the language of a priest, a self-righteous uncle and a used car salesman combined. Someone who limps toward emotional statements, not newsworthy conclusions. But subjective commentators have been around since news existed for commentators to comment on. What is so wrong with this particular species of pundit? Their language is emotional, their popularity troubling, their arguments simplistic and infantilizing. They have personalized the public sphere by making their shows into personality- driven universes with similarly subjective truths. And they are, above all, the captains of what David Foster Wallace calls a “peculiar, modern, and very popular type of news industry, one that manages to enjoy the authority and influence of journalism without the stodgy complaints of fairness, objectivity, and responsibility that make trying to tell the truth such a drag for everyone involved.”

But for the moment, let’s complete the O’Reilly-as-preacher analogy. He is the local cleric. You, a loyal viewer, are a member of his congregation. And yes, you are faithful. Imagine that you support him through the whole dizzying catalog of his ridiculous campaigns: The boycott of France! The War on Christmas! The ban on Ludacris! You even may have bought The O’Reilly Factor for Kids for your children. The question, maybe, is this: who are you, you who take as communion his specious claims and who wed yourself to his rhetoric? Who are you, why have you resorted to watching him, and how will you behave because you watch him?

Dracula in Charge of the Blood Bank

There is a difference between the “public interest” and “what interests the public.” News should not just be an exercise in amusement; it should better society through its integrity and objectivity. So argued Newt Minow, FCC Chairman, when he urged networks to uphold a higher standard of journalism, instead of just pursuing ratings, in his 1961 “Vast Wasteland” speech to the National Association of Broadcasters. This is the most worrying thing about pundits, suggests Steve Rendall, senior analyst at Fairness and Accuracy in Reporting (FAIR): the extent to which pundits are ruled by, and feed, the corporate interests which support their existence. Many media commentators suggest that although news has always been a business, there once existed a greater consciousness of journalistic integrity.

Or is that just nostalgia for the good old days? Maybe, but it’s a nostalgia borne out by the rise of corporations and the deregulation of the Reagan Era. During the Regan Era, we saw the refutation of the Fairness Doctrine, an FCC policy which required broadcasters to present controversial issues of public importance, and to cover such issues in a “fair and balanced way.” Today, the economic interests driving news are everywhere evident: See Michael Powell’s chairmanship of the FCC (which Rendall describes as “Dracula in charge of the blood bank”). See CBS Chairman Sumner Redstone’s suggestion in 2004 that he would have voted for Kerry in the national election if not for financial interests. See General Electric’s ownership of NBC.

Of course, the pundit culture does not just happen; it only becomes possible under certain circumstances, not all of them economic. Pundits are a product of the national imagination once it has been diffracted into its extremist right elements. Which presents the question: Why are pundits so overwhelmingly conservative? Blowhards from the left—think Al Franken, Michael Moore—have appeared, but they are nowhere near as powerful or systemic as those on the right. Rendall recalls his experience on a radio show on KIRO, a Seattle-based network, debating with conservative pundit Mike Siegel, who claimed that liberal radio pundits were rare because liberals simply had nothing funny or entertaining to say. Rendall countered, “Mike, the only place liberals aren’t funny or entertaining is on the radio, and that’s because they’re not ‘on’ talk radio.”

Doubtful. But what’s certain is that punditry tends to the right and thrives on the public crucifixion of liberal ideas. The image of weak liberals has been ingrained into the flesh of pop culture under varying names: Pat Buchanan’s “mainstream media’s liberal bias,” O’Reilly’s “cowards,” Ann Coulter’s “traitors,” Alan Colmes’ liberal straw man, all presented without protective irony or the suggestion that a political spectrum, rather than diametrically opposed armies of right and left, may exist. Instead, there’s a right-heavy dose of punditry with a heavy religious bent. “If a young person with conservative beliefs wants to feel connected to someone political in the media, and they’re not religious, there aren’t a lot of options,” says Dana R. Fisher, Assistant Professor of Sociology at Columbia. All of which may explain why O’Reilly and people like him are more preacher than politico.

My Boat is Swifter Than Yours

But how much influence do pundits really have? “God help us if the pundits did have influence!” says Herbert J. Gans, Robert S. Lynd Professor of Sociology at Columbia. Gans points out that although notoriously pundit-heavy Fox News receives high ratings by cable TV standards, their audience is tiny compared to the other networks. Fox rarely attracts more than 3.5 million viewers, compared to the 40-million average combined audience for CBS, ABC, and NBC’s evening news shows. On the question which has divided media studies since it was born a century ago—how influential is the media?— Gans falls on the side which argues that the mass media have limited or minor effects; the other side, the so-called hypodermic theory, insists that the effects are unlimited, and directly affect behavior. An extension of the latter view suggests the following: television violence is followed by real-life violence, erotica encourages promiscuity.

This, Gans argues, is a mistake. His 2003 book Democracy in the News asserted that political opinions are formed by so many factors, the news watched by so increasingly few, and that news stories are so much more significant than the journalists who broadcast them, that newscasters are rather unimportant to the forming of popular political opinion, especially when they are competing with family, friends, and the water cooler as news sources.

Will a pundit who takes on the emotionality, casual manner, and informal language of a family member or friend therefore be more influential on the news audience than a conventional newscaster? Gans declares that when newscasters throw off the trappings of formality, they also surrender “what the networks really have to sell—authority.” He explains that when newscasters start to sound like family and friends, “They’re saying, ‘[what I’m reporting] really isn’t terribly important.’ These techniques are things which might work in local news.”

This, of course, speaks to the deeply local quality of emotional punditry. It answers the question we asked about the O’Reilly viewer, the question of “who are you?” The answer is that the people who watch such pundits are small but loyal groups of conservatives who feel themselves to be on the edge of political extinction, at the margins of a vast liberal culture. They are not repulsed by the fact that pundits seem to reside in a limbo between entertainer and journalist, because pundits, Gans explains, “preach to the choir” above all. Pundits are small people whose outrage casts large and farcical rhetorical shadows. But if pundits are so unimportant, how do we explain events which suggest that pundits are undeniably powerful?

Take the Swift Boat Veterans for Truth. Formed to oppose John Kerry’s candidacy for president, they aired vicious attack ads questioning Kerry’s military record in a campaign that struck at many of Kerry’s top selling points— Veteran activist! Military expert! Human!— and was probably instrumental in toppling his potential presidency. But consider: the Veterans for Truth were made up of Vietnam veterans, but almost none of them served with Kerry. Founder John O’Neill had been recruited by the Nixon White House to oppose Kerry’s antiwar activism in the ‘70s, according to Nixon aide Charles Colson, and many other Swift Boat members had explicit ties to the Republican Party. The group had no legitimacy. Yet after being propelled to the height of media attention by Sean Hannity, almost no one in mainstream news treated the Swift Boat story with the cynicism and outright disbelief it deserved.

Doesn’t this show that pundits do have influence? That they might be the real kingmakers, the real peddlers of policy, in a tabloid age? Not necessarily, Gans replies, who sees Hannity’s role in the episode as that of “the messenger, causally necessary but not sufficient.” The story was still larger than the pundit who publicized it. All the things that make a pundit a pundit and not a newsman— the aggression, the emotion— took a backseat to the story itself.

Here’s an idea that strikes a balance between Gans’ skepticism and the hypodermic hysteria that opposes him: pundits don’t usually have influence, but they can when circumstances allow them to become the architects of national myths. Pundits usually traffic in petty fictions, but sometimes they hit upon stories so large, so broadly appealing, so apparently urgent, as to lift punditry out of its obscurity. It needs to be just the right kind of story in just the right kind of political climate: a perfect storm belched out of the political machine when emotional outrage plus national concerns are mixed with the mythmaking that only pundits can provide. One might argue that we give pundits a chance at a perfect storm every four years.

The Theater of the Absurd

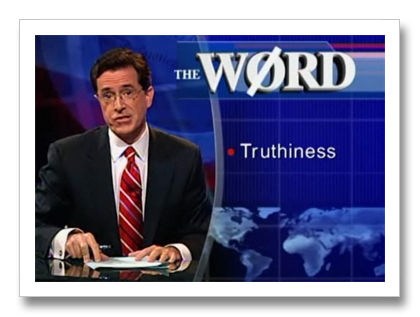

The best—and truest—fairytales on television do not come from Franken and Hannity. Theirs are dim fables. They come from two men named Jon Stewart and Stephen Colbert. Many viewers— many of them young, many of them college students—have turned to Comedy Central’s The Daily Show with Jon Stewart and its spinoff, The Colbert Report, for critical and satirical news analysis presented with an utter lack of seriousness. In fact, during the 2004 US presidential election, the show received more male viewers in the 18-34 year old age demographic than Nightline, Hannity & Colmes and all of the evening news broadcasts.

On The Daily Show, the news correspondents are fake; however, the harassment of politicians and policymakers is real, and the show’s status as a comedy show paradoxically allows Stewart to ask hard-hitting questions often evaded by the networks. The Colbert Report, manned by Stephen Colbert as a right-wing blowhard modeled on Bill O’Reilly, caricatures punditry through Colbert’s sarcastic “poorly informed, high-status idiot” approach.

The fact that some of the best and most provocative political critiques in mainstream culture are clothed in the words of comedy show hosts who are at once more entertaining and more incisive than pundits is as ridiculous as the fake news itself. Almost as ridiculous as the degree to which their viewers are informed: an Annenberg Public Policy Center survey found that Daily Show watchers were more informed about the 2004 presidential election than people whose main news sources were the national evening newscasts of ABC, CBS, and NBC, as well as those who mostly read newspapers. However, a 2006 paper in American Politics Research found that watching The Daily Show’s “theater of the absurd” made college students more cynical of mainstream media and the electoral process itself—an attitude that has been linked to lower rates of political participation and engagement.

Are Stewart and Colbert rearing a generation of well-informed but apathetic citizens? Perhaps we should look to the children of the Cold War for an answer. Like ours, that generation was raised in an atmosphere of suspicion over internal subversion and external threat from an ideological enemy. They, too, were fighting with the professed aim of spreading democracy, while the possibility of nuclear war loomed large. And that period, like ours, produced blistering works of political satire. If pundits like O’Reilly are the successors of McCarthy rather than any legitimate journalist, perhaps Stewart and Colbert are the heirs to the black comedy of Dr. Strangelove. And the tragedy of satire, however ridiculous, is that it is the strangled reflection of a troubled reality. Yes, it is reflective; our pundits are not simply cultural phenomena which exist outside of ourselves and whom we can easily destroy. In their grand angry gestures and emotional language is the expression of our own private rage colliding with the public sphere. Pundits simply voice and encourage a political disunity which already exists. The words of pundits are not the weapons of political battle; they are the lyrics to the battle hymn.